Revisiting a scent wheel1:57

Revisiting a scent wheel1:57

What you see is what you smell

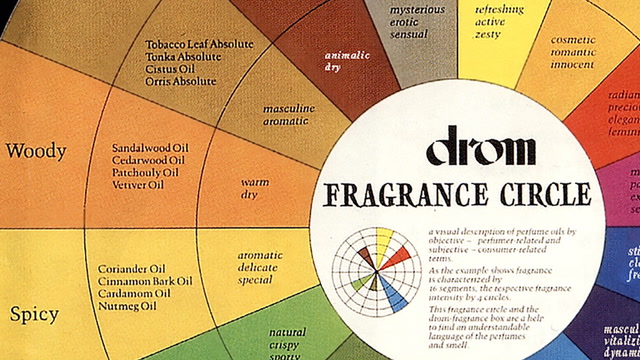

Circles and wheels are common formats used for knowledge visualization in different contexts. The color wheel organizes the relationships between primary, secondary and tertiary colors and visualizes color relationships. In the field of music the circle of fifths visualizes the relationships between major and minor keys. Accordingly, wheels are used to highlight relationships, identify families based on fundamental similarities, and illustrate different grades of intensity. In the olfactory domain, wheels were used in the 16th century to classify the smell of urine for medical purposes. Since the early 20th century the wheel has become a popular format in perfumery. In the world of perfumery the fragrance wheel serves as a handy tool for classifying perfumes. However, many questions are more puzzling than a neat visual design might suggest, as Christophe points out in this clip.

Step by step6:01

Step by step6:01

There is more than meets the eye

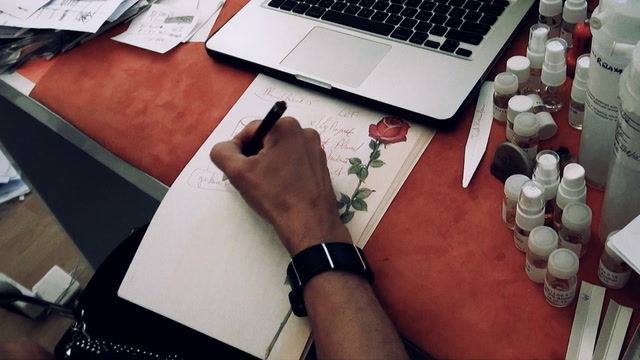

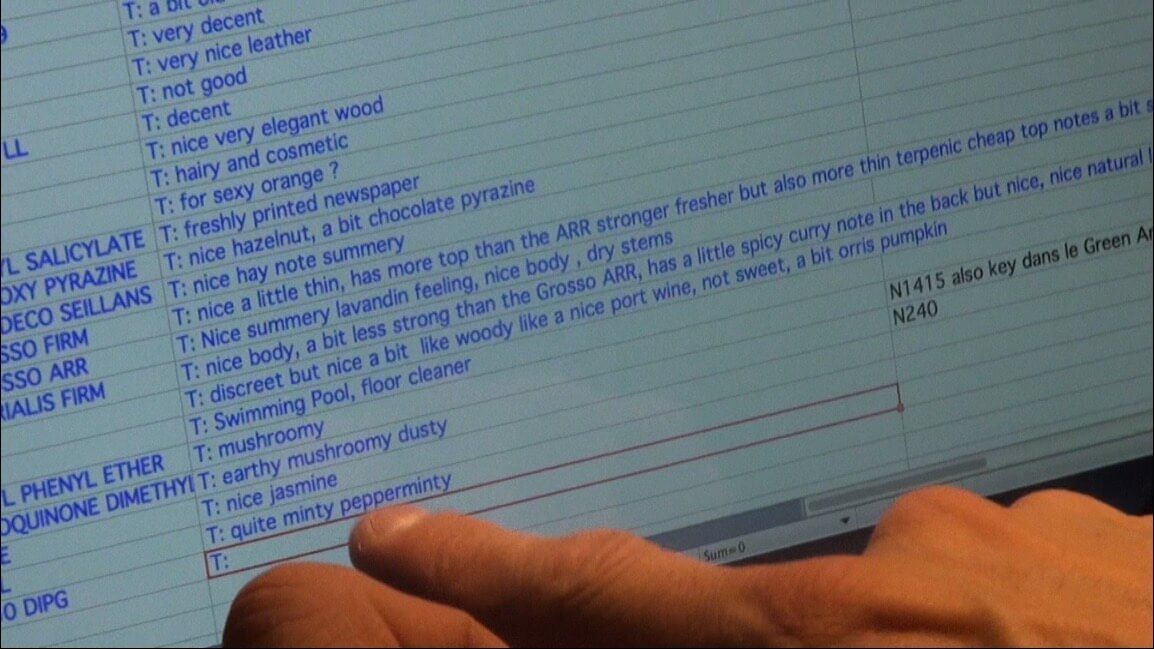

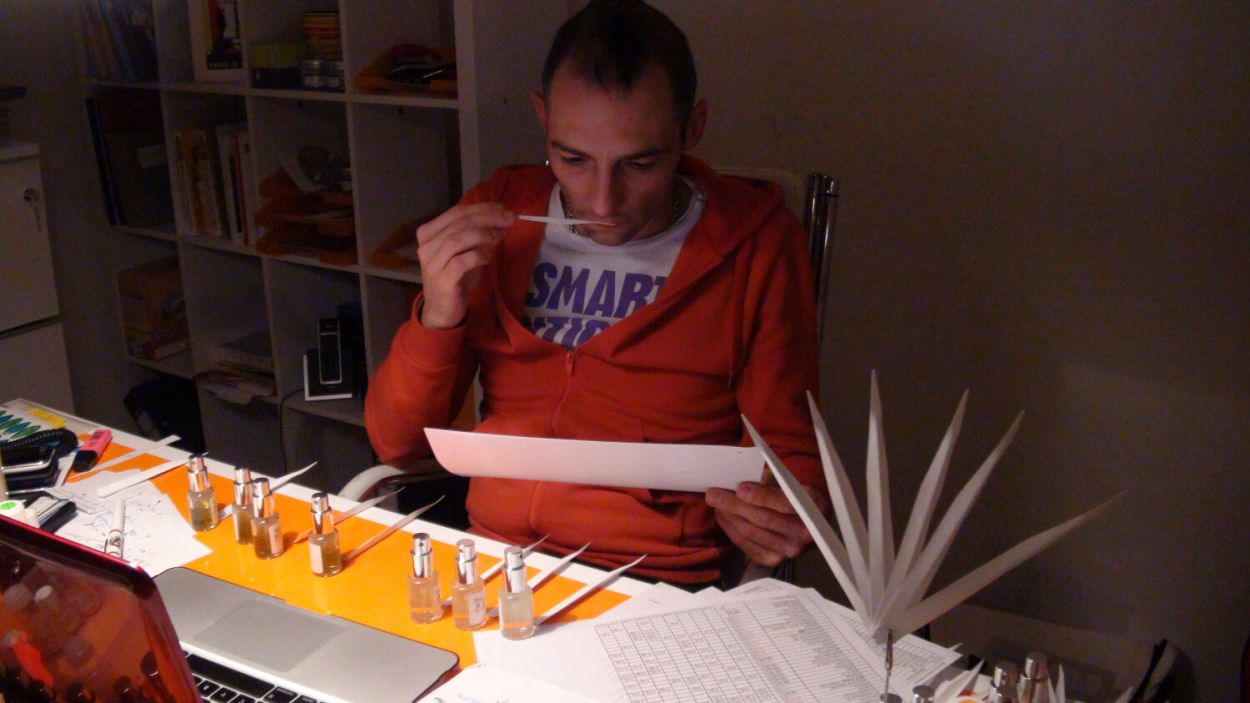

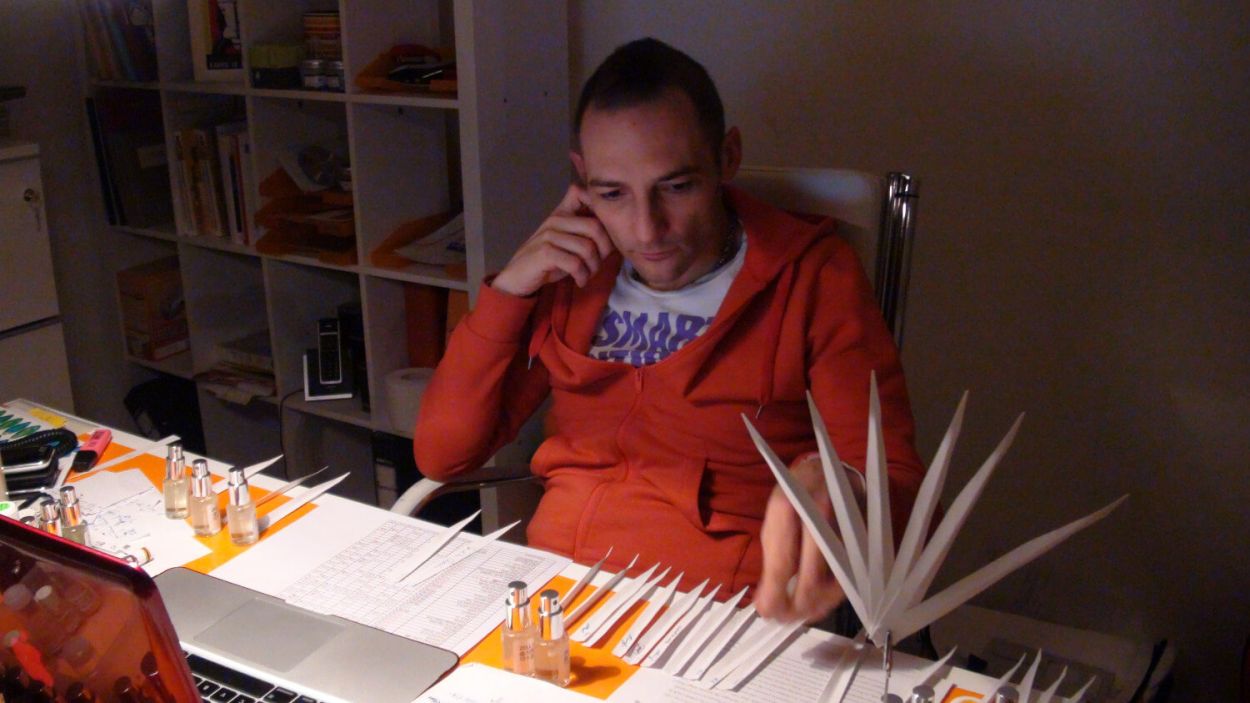

At its core, the practice of perfumery has not changed very much since Renaissance times. The process can be described along a sequence of clearly defined steps: The perfumer starts with some vague ideas which are evoked by certain olfactory ingredients. Thereafter, this rather open process is narrowed down to a precise formula determining the perfume composition in quantitative terms - how much of each material is needed to achieve the ideal balance. Accordingly, the formula is precisely weighed in the laboratory. Each step is accurately documented on a spreadsheet. Using paper strips the perfumer smells and evaluates the scent. Alternative variations are analyzed. The formula is then modified based on detailed analysis. This sequence of steps is repeated until the olfactory experience meets the expectations of the perfumer: Calculating the formula, weighing, evaluating & analyzing.

Nobel laureate Herbert Simon once analyzed how in oil painting every new spot of pigment laid on the canvas creates some kind of pattern that provides a continuing source of new ideas to the painter. Hence, the painting process unfolds as a process of cyclical interaction between the painter and canvas in which current goals lead to new applications of paint, while the gradually changing pattern suggests new goals. In the case of scent development, the cyclical interaction involves the competent use of additional objects (e.g. the formula). However, the practice of perfumery cannot be reduced to this technical dimension. Instead, it is also a meaning and sense-making activity. «To become a perfumer you don’t learn to smell like one – you learn to think like one», Avery Gilbert once noticed. This clip provides a quick primer on this practice.

Facing A Brainiac2:14

Facing A Brainiac2:14

A good briefing inspires and ignites a perfumer.

The development process for a new perfume involves coordination across various design disciplines: The creative director is not only responsible for the perfume’s name and theme. He is also in charge of preparing the perfume concept (or «brief») and coordinating the overall product fabrication. The photographer shoots the campaign photography. Packaging designers create the bottle, cap and box that will eventually house the perfume when it is finally displayed on the department store shelf. A writer composes press releases and other texts used to market the perfume. Finally, there are the perfumers who develop the fragrance. An additional challenge is that the above designers are often geographically dispersed throughout the world. How is organizing accomplished in such a context that requires coordination among all the designers? How come it does not impede their creative freedom?

In this case the independent designers and their sub-products are coordinated by means of a visual concept which consists of three collages, known as a «mood board.» A mood board is an aesthetic device that connects senses and emotion. It is able to encourage multiple conceptual interpretations while also having a directing and aligning effect. But do the perfumers really care about the concept? For Christophe it is clear that the concept goes beyond the technical brief that dictates raw materials and identifies a target consumer. The concept challenges the perfumer’s creativity. This clip reveals the perfumer’s personal attachment to the concept and its performative qualities: «It is a brainiac».

(De)briefing a scent2:36

(De)briefing a scent2:36

What is challenging about talking about scents? Can scents have structure? How many dimensions does a scent have?

A meeting with Sebastian Fischenich, the creative director of Humiecki & Graef, provides an opportunity to reflect on the state of the project. The perfumer presents alternative modifications and clarifies next steps with the creative director. In this case the two evaluate alternative scent «structures,» an initially surprising metaphor used to capture the fleeting nature of the olfactory experience.

Sketching a scent2:19

Sketching a scent2:19

The ephemeral materiality of scent eludes the common conventions of visualizing.

Instead, the qualities inherent to the sense of smell remind us of the limitations of our visual culture: But can scents be rendered visual? Pyramids are widely used forms of visual representation when developing or discussing a fragrance. This clip documents Christophe speaking to a client over the phone. Actually, it is a briefing for a new candle scent. After listening to the client Christophe outlines his ideas. Interestingly, he continuously visualizes his ideas: A scent is drawn. Is this merely an illustration? We doubt it. Since the days of the historical Bauhaus vision has been recognized as a «cognitive power in its own right». The ongoing discourse on visual culture reflects on the visual dimension and its implications for society, culture and business. Thus, the agency of sketches and even the seemingly most banal visual artefacts is increasingly acknowledged. There is more than meets the eye.

Fragrant upcycling2:56

Fragrant upcycling2:56

Garbage smells.

Anyone with a nose knows that trash can stink. It is this truism of modern life that this clip challenges: Trash can smell nice. According to our fieldnotes Christophe casually once remarked: «The garbage often smells good. And: If you want to remake it, good luck». Hence, smelling trash is a recurring theme in a perfumer’s studio. This clip, however, shows how smelling a perfumer’s trash bin can open a discussion on sustainability in the fragrance industry and envision a future of fragrant upcycling.

Encounter with a perfume icon1:05

Encounter with a perfume icon1:05

Shalimar is an iconic perfume. But why is it relevant today?

Successful cultural products blend familiar and novel elements. On the one hand, consumers relate to scents that remind them of others they like. On the other hand, they also appreciate the unexpected pleasure of the new. Depending on the overall position of the scent, the actual relatedness of a perfume can vary from that which is entirely derivative of an existing scent, to that which is clearly building on an existing scent, to that which is predominantly original but shows subtle references to an existing scent. This video captures the moment when a modification reminds Christophe of Shalimar, a great perfume created by Jacques Guerlain in 1921. Its story is part of the wider social and cultural matrix in perfumery. Accordingly, the composition was inspired by Mumtaz Mahal, the wife of Shah Jahal, a 17th century emperor of India. Traditionally, the imitation or matching of an iconic perfume serves as a method of learning the craft. In this situation the sudden connection to Shalimar prompts Christophe to return to the formula. To his surprise, the formula is rather different from Shalimar’s. Yet, the scene documents the remaining influence of an historical icon for cultural production.

Wet dog: Chasing the villain5:52

Wet dog: Chasing the villain5:52

This clip features a puzzling mystery Christophe encounters when developing a new scent for Strangelove NYC

In most cases, a perfume is meant to be a pleasurable odor. Technically, it is a mixture of essential oils, aroma compounds, and solvents used to provide an agreeable scent. Yet, the process is more complex than often explained. A useful fragrant ingredient might turn out to be an objectionable odor in a specific combination or concentration: Skatole (from the Greek root skato – meaning «dung») for example, is an indole with a strong fecal odor at high concentrations, but it is often used in perfumery at a much lower concentration where it has a pleasing floral scent. Following the development of a jewel-like fragrance we witnessed how Christophe Laudamiel and Christoph Hornetz suddenly discovered an unpleasant facet, an annoying animalic note. Laudamiel calls it a «wet dog» that only appears after some delay. The two perfumers are puzzled. The phenomenon seems to be really special, if also undesired. They investigate the composition, ingredient by ingredient. In the end, the detective search for malodor delivered a suspect for which Christoph Hornetz had noticed the same unexpected effect in other previous instances: Natactone®. The odor of this chemical compound is often described as «tropical coconut, tonka bean and tobacco». Thus, this clip tells the detective story of a puzzling mystery.

Family dispute3:18

Family dispute3:18

This video empowers consumers to challenge the salesperson upon their next trip to a perfume store!

At most perfume stores it is common to classify scents by olfactory families. For instance, a department store perfume salesperson identifies the consumer’s passion for a flowery or spicy note and provides more samples from these olfactory families. In encounters such as this, a consumer might easily feel inferior to the salesperson’s expertise. However, in observing the perfume field, we have noticed that even among experts there are highly personal systems of classification that vary from perfumer to perfumer. We asked Christophe Laudamiel and Christoph Hornetz for a set of sample olfactory materials that could help us to better understand some of the everyday practices in the field. One of the perfumers came up with a list of materials grouped by families. One night, we discussed the list over wine and cheese with the two perfumers. On this occasion we learned how even two perfumers who had closely collaborated for several years can quickly disagree about commonly shared olfactory conventions and classifications. Bear in mind that the perfumers talk about single molecules whereas commercial perfumes are composed of several dozen different molecules. After watching the video the viewer should feel empowered to challenge the salesperson upon their next trip to a perfume store!

A naïve child3:37

A naïve child3:37

How does Christophe approach even well known raw materials?

Students often think of learning as an unidirectional accumulation of knowledge. Critical scrutiny, however, reveals that prior knowledge might even hinder efforts to learn or acquire new knowledge: As the British social scientist Gregory Bateson once said: «You can't live without an eraser». Hence, practices of unlearning are essential for all types of knowledge work. In the case of Christophe we often saw him approaching even well known raw materials as if he had never smelled them before. This made us wonder and we asked him about this practice. In fact, there is reason to believe that creative practices hinge upon this kind of open approach.

Melt my heart0:50

Melt my heart0:50

We witness a magical moment.

Christophe is putting his left hand on his chest. His eyes express true joy. The perfumer is almost bursting with pleasure while declaring his love for camomille. Christophe recalls the name Elizabeth Ganes, the founder of the high-quality brand StrangeLove NYC mentioned in her briefing: Melt my heart. At the same time the scent affects Christophe emotionally. He cannot control his feelings: Christophe literally embodies the claim: Melt my heart. In many cases a perfumer does not even know the name of the scent when creating. Does this little thing make a difference to the quality of the final composition? Based on this scene one might think so.

Envisioning a perfumista0:54

Envisioning a perfumista0:54

Once, Christophe retrospectively envisions a persona who could wear his creation.

Perfumes are usually developed with a specific user in mind. Sometimes even stereotypes are used for briefing a perfumer. The former New York Times perfume critic Chandler Burr once even presented a parody of this type of briefing: «We want something for women. It should make them feel more feminine, but strong, and competent, but not too much…». Following Christophe’s work we hardly ever witnessed anything like this. Instead, it was the scent and its aesthetic quality that guided the design process.

Once, however, after the development of Blask had been completed for a while, Christophe retrospectively envisioned a persona who could wear this fragrance. Interestingly, his persona very much resembles the user, Mark Behnke, a well known perfume blogger, had in mind when reviewing this creation: «Blask is not a fragrance for everybody but if you are someone looking for a line that takes risks and challenges your perception of what perfume could be, Blask is something you need to try».

The title of this clip alludes to the growing enthusiasm for perfumes. A perfumista professes the culture of olfactory hedonism. Some perfumista might identify themselves as «fragraholics», «perfumaniacs» or «fragonerds» (just to mention a few labels popular within the subculture). A perfumista often wears an exotic fragrance that distinguishes itself from the middlebrow tastes of most people. One might think of Andy Warhol as a forerunner who once openly talked about his fondness for esoteric fragrances:

«Sometimes at parties I slip away to the bathroom just to see what colognes they’ve got. I never look at anything else— I don’t snoop—but I’m compulsive about seeing if there’s some obscure perfume I haven’t tried yet, or a good old favorite I haven’t smelled in a long time. If I see something interesting, I can’t stop myself from pouring it on. But then for the rest of the evening, I’m paranoid that the host or hostess will get a whiff of me and notice that I smell like somebody-they-know.»

Sometimes this passion for perfumery grows from an interest in chemistry and might rise to further practices. Some perfumista indulge in excessive perfume collecting. Others research for educational material, learn the basics of perfume creation and start as DIY perfumers. Another group of perfumista might start to write perfume reviews or publish related video content on youtube. All in all, they give rise to an increasingly discursive consumer culture. What started on the fringes eventually changes the rules of the game in the fragrance industry.

Evaluative moments2:33

Evaluative moments2:33

Three professionals engage in smelling and discussing an advanced modification of Meltmyheart, a fragrance by StrangeLove NYC.

We see how Christophe Laudamiel, Christoph Hornetz and the flavorist Marlene Staiger spontaneously share their impressions and associations. Apparently, there is no one way of evaluating a scent. A closer look reveals how micro-practices of smelling and using blotters can differ. Christophe is particularly interested how the other two experience a certain effect that he describes as «hot metal effect». The subtitles show how the three professionals cannot agree on what the dominant note of this scent smells like: caramel, coconut and hot metal stand next to each other. A shared interpretation of what they are actually smelling seems to be rather unimportant. Yet, something is achieved in this communication. It is neither explicit agreement nor disagreement. Instead it is the affective experience the three professionals express and collectively interpret as «good». And it is this affective experience that might be key to understanding how organizing is accomplished in a creative context. Is it possible that affects really constitute an organization?

Taking perfumes to nightlife0:57

Taking perfumes to nightlife0:57

The ephemeral materiality of scent deeply impacts on how a perfumer can balance life and work. The perfumer’s body is a resource as well as a constraint.

Moving from paper testing strips to the skin can drastically change the overall experience of a perfume. What might be banal everyday knowledge has far reaching consequences for a professional perfumer. The skin of a perfumer is a constraint in the process because there are hardly more than three spots on each arm to spray. Once sprayed on the arm the scent will stay until it has completely evaporated. How long this takes is a matter of the scent’s molecular structure. Hence, a scent does not comply with an organization’s time regime. Instead, the involvement of the perfumer’s body makes the perfumer take his work home, or in this case, to the bar. In this clip, set in a bar late at night, Christophe notices a few molecules on his arm, and casually evaluates the set of recent creations. The undisciplined nature of scent blurs the boundaries of work and non-work.

Mundane lab work4:00

Mundane lab work4:00

Perfumery is not always glamorous. Creativity unfolds in a nexus of mundane work practices.

Perfumery is practiced in a lab. The lab serves several functions. It is a storage space for the ingredients that are alphabetically shelved. More sensitive materials are kept in a designated refrigerator in the lab. Moreover, the lab provides specific tools and equipment (e.g. scientific scales). As a special workplace the lab is the place for creating solutions of solid materials or weighing formulae. The lab also serves as the perfumer’s archive where modifications of completed projects are stored. All in all, the lab provides access to the world of the volatile molecules. While observing Christophe’s creative process we were surprised how often he went to the lab to reconnect to his material base.

Leading Perfumery schools often expect a formal education in chemistry. For example, Christophe Laudamiel studied chemistry in France and eventually earned a Masters degree from MIT. Nevertheless there are other eminent perfumers who never studied chemistry: Francois Coty, Ernest Beaux, and Jean Carles, to name three titans of perfumery. Thus, the relevance of a formal education is certainly debatable. But there is no doubt that a profound understanding of chemical compounds, how they behave or react with each other is essential. At the end of the day the scent development process must follow scientific practices and comply with technical standards and procedures. Hence, this clip zooms into the mundane, less spectacular aspects of lab work. The current discussion of design thinking often reduces design practice to an immaterial, intellectual problem solving technique. In this one-sided context, a closer look at mundane lab work put renewed emphasis back into material practice.

Making of Hemingway in 6-Major4:08

Making of Hemingway in 6-Major4:08

An upcoming gallery show changes the rules of the game.

«Clients are the difference between design and art», as a common saying goes. In fact, it is the client who sets the goals, decides on the budget and approves the final scent. Hence, perfumers work under constraints defined by the client whereas creative work is often associated with freedom and autonomy. Yet, constraints can also be helpful because they stimulate creativity rather than suppress it. This clip shows how Christophe copes with a set of self-defined constraints and highlights the importance of independent work for the creative practice. A few days later, the project Hemingway in 6-Major was actually exhibited at a fancy gallery in Chelsea.

Key quotes with this tag

Images with this tag

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

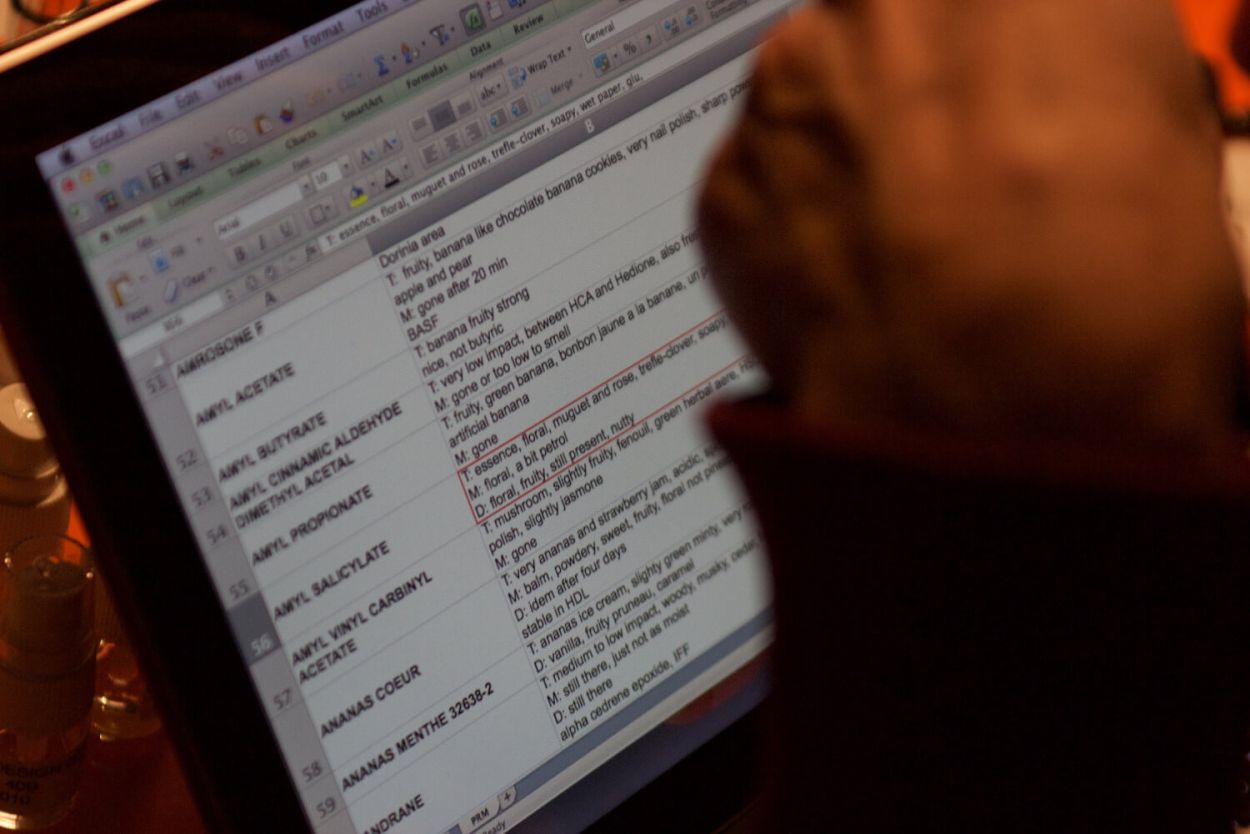

Christophe consulting his personal knowledge base.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel at his desk - en passant smelling his palms?

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

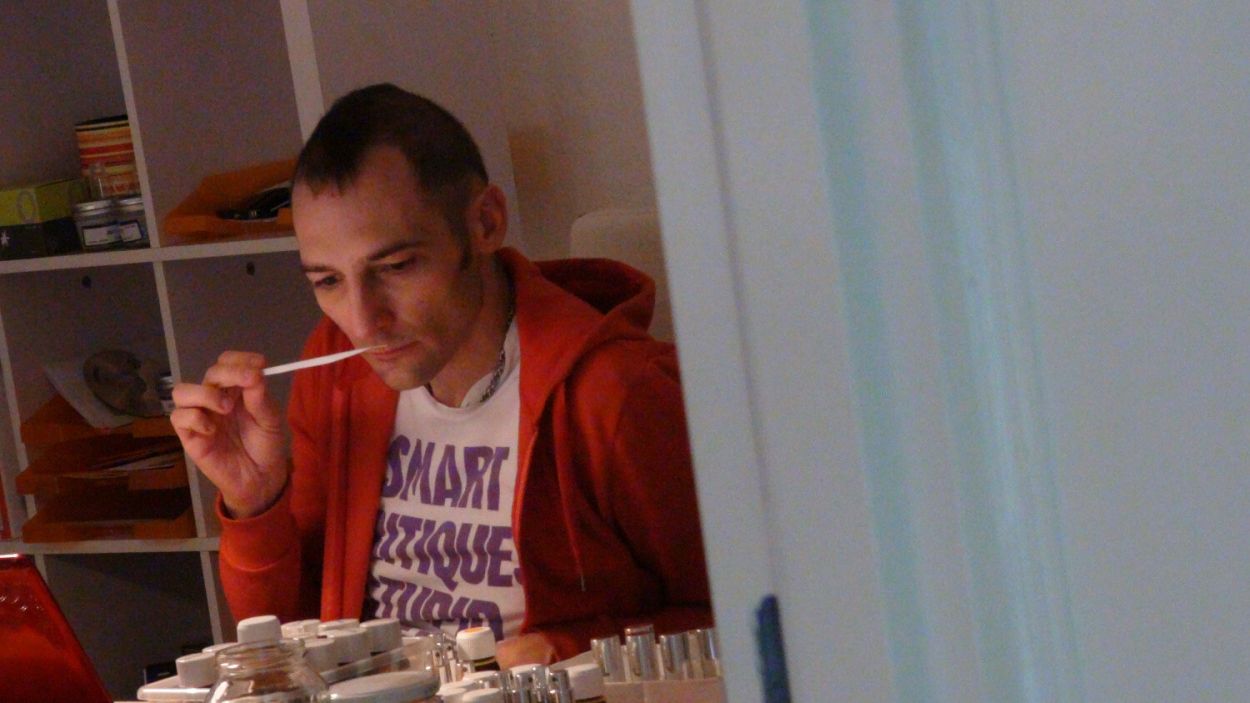

Christophe Laudamiel smelling at his desk.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel running a family workshop at an olfactory storytelling festival in Solothurn, 2019.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

A snapshot of Christhope Laudamiel’s knowledge base.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel evaluating multiple modifications.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel working on his laptop.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Searching for scent ingredients in the laboratory can quickly develop into a fascinating journey.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel focusing on a modification.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel & Christoph Hornetz attending a panel discussion in the context of The Art of Scent at the Museum of Arts and Design, New York. During the event it was remarkable how the panellists involved Christophe who was only in the audience and forwarded questions to him as if he were on the panel.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Claus Noppeney, Christophe Laudamiel & Nada Endrissat after a panel discussion at an olfactory storytelling festival in Solothurn, 2019.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

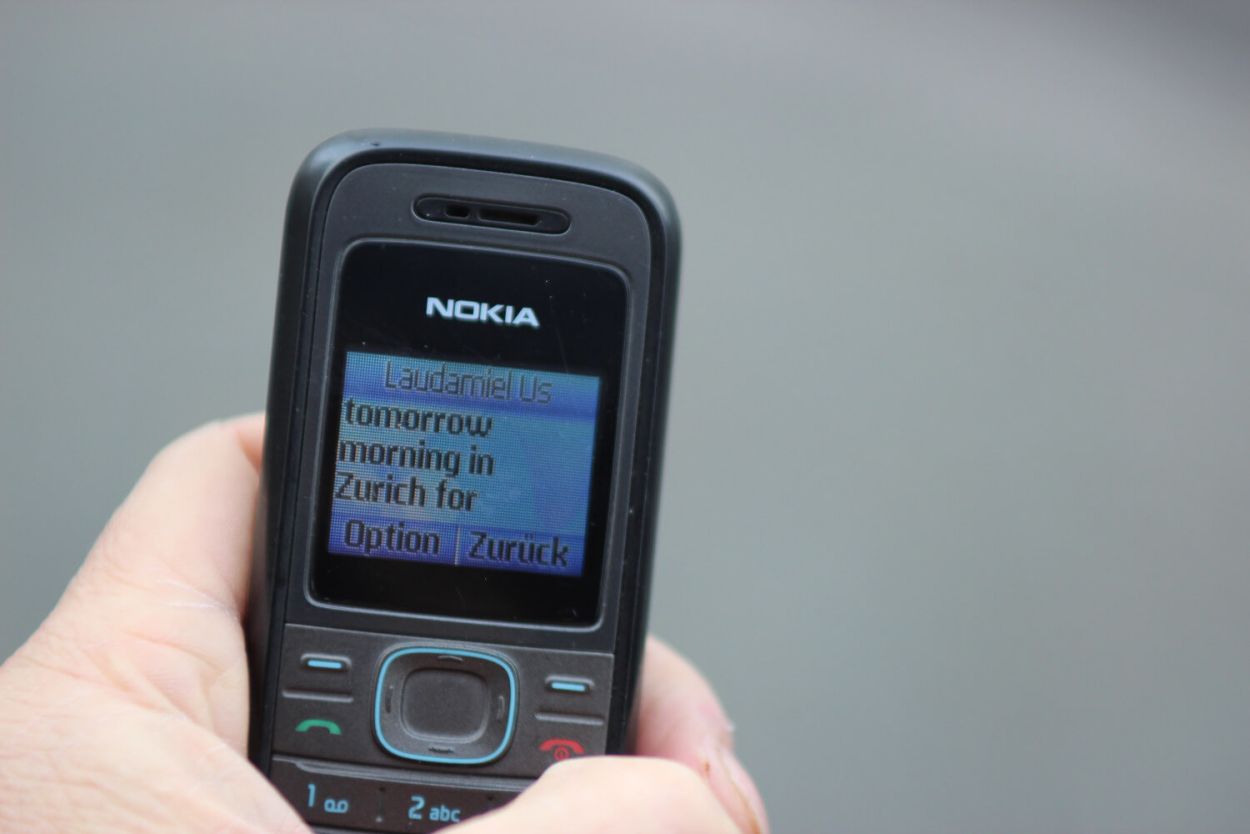

Communicating in the field: SMS on Claus’ mobile phone.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel, Nada Endrissat & Claus Noppeney discussing research results at an olfactory storytelling festival, Solothurn 2019.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christoph Hornetz & Christophe Laudamiel discussing at Dreamair, New York.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

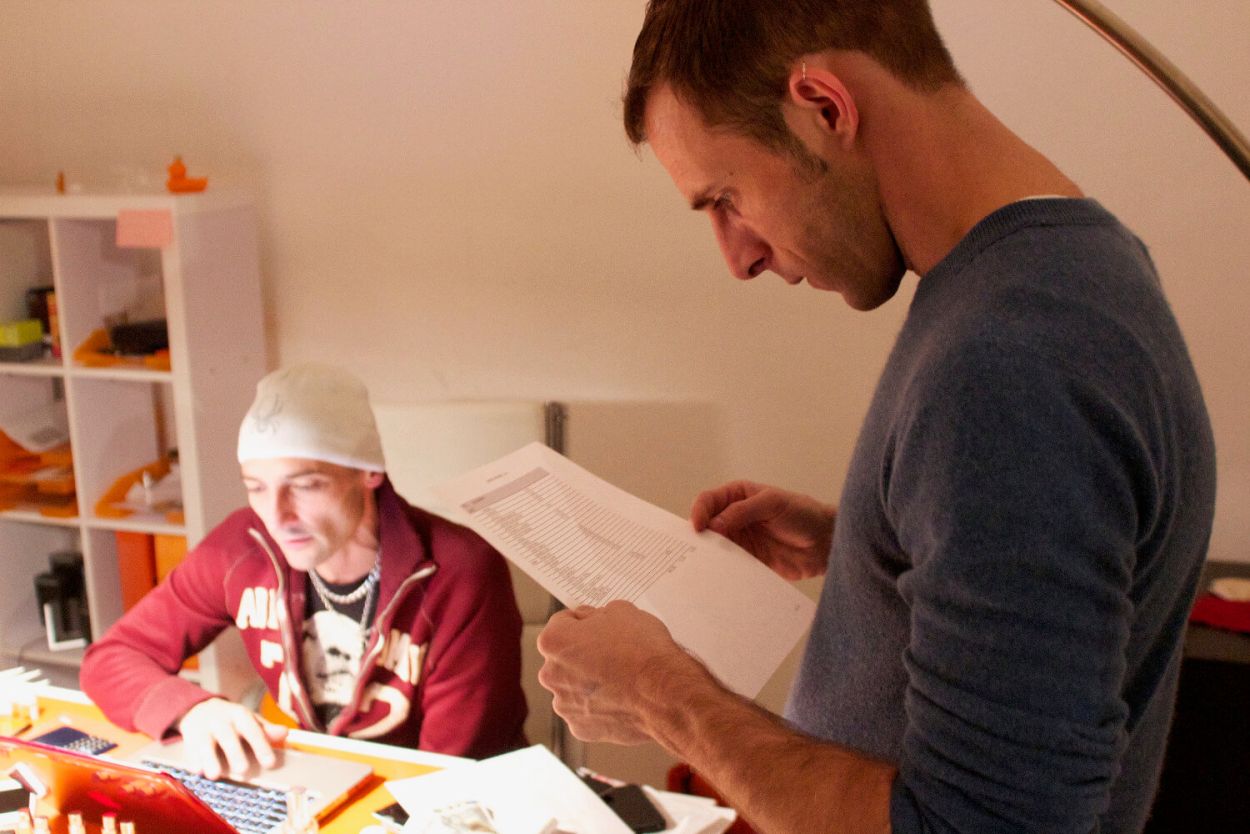

Christophe Hornetz discussing a formula with Christophe Laudamiel at Dreamair in Berlin.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel at Dreamair, Berlin.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christoph Hornetz & Christophe Laudamiel evaluating combinations of different scents and different resins.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel getting organized at his desk.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel analyzing a set of modifications. There is a video documenting this type of work further.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Claus Noppeney interviewing Christophe Laudamiel at Dreamair, Berlin.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel seeking another nose.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

En passant, Christoph Hornetz and Christophe Laudamiel are smelling and sharing first impressions.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel evaluating different resins.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christoph Hornetz & Christophe Laudamiel evaluating combinations of different scents and different resins (e.g. when trying to smell pepper).

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel smelling a scent on his hand.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel smelling two modifications in a relaxed body posture.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel analyzing a set of modifications. There is a video documenting this type of work further.

All Tags

- Affect

- Ambience

- Ambiguity

- Analogy

- Analyzing

- Artifact

- Associating

- Beyond words

- Briefing

- Classifying

- Consuming

- Creating

- Culture

- Deciding

- Desk work

- Embodiment

- Ephemeral

- Ethnography

- Evaluating

- Experimenting

- Hemingway

- Humiecki & Graef

- Industry

- Ingredient

- Interaction

- Labelling

- Laboratory

- Metal

- Modifications

- Mundane work

- Orange Flower

- Paper

- Presenting

- Sense-making

- Shalimar

- Smelling

- Storytelling

- Still life

- Strangelove NYC

- Translating

- Visual

- we are all children

- Words