Encounter with a perfume icon1:05

Encounter with a perfume icon1:05

Shalimar is an iconic perfume. But why is it relevant today?

Successful cultural products blend familiar and novel elements. On the one hand, consumers relate to scents that remind them of others they like. On the other hand, they also appreciate the unexpected pleasure of the new. Depending on the overall position of the scent, the actual relatedness of a perfume can vary from that which is entirely derivative of an existing scent, to that which is clearly building on an existing scent, to that which is predominantly original but shows subtle references to an existing scent. This video captures the moment when a modification reminds Christophe of Shalimar, a great perfume created by Jacques Guerlain in 1921. Its story is part of the wider social and cultural matrix in perfumery. Accordingly, the composition was inspired by Mumtaz Mahal, the wife of Shah Jahal, a 17th century emperor of India. Traditionally, the imitation or matching of an iconic perfume serves as a method of learning the craft. In this situation the sudden connection to Shalimar prompts Christophe to return to the formula. To his surprise, the formula is rather different from Shalimar’s. Yet, the scene documents the remaining influence of an historical icon for cultural production.

Excel-ing a scent1:40

Excel-ing a scent1:40

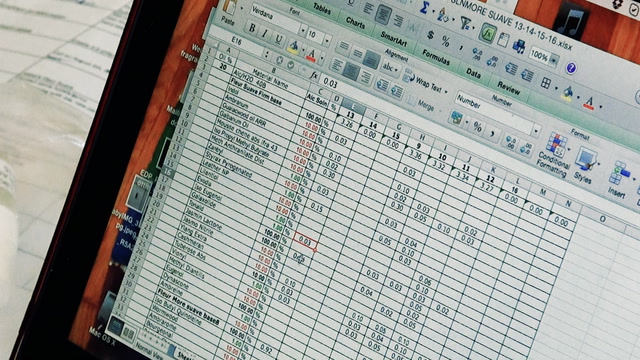

Have you ever thought that the fleeting experience of a scent boils down to something as prosaic as a spreadsheet?

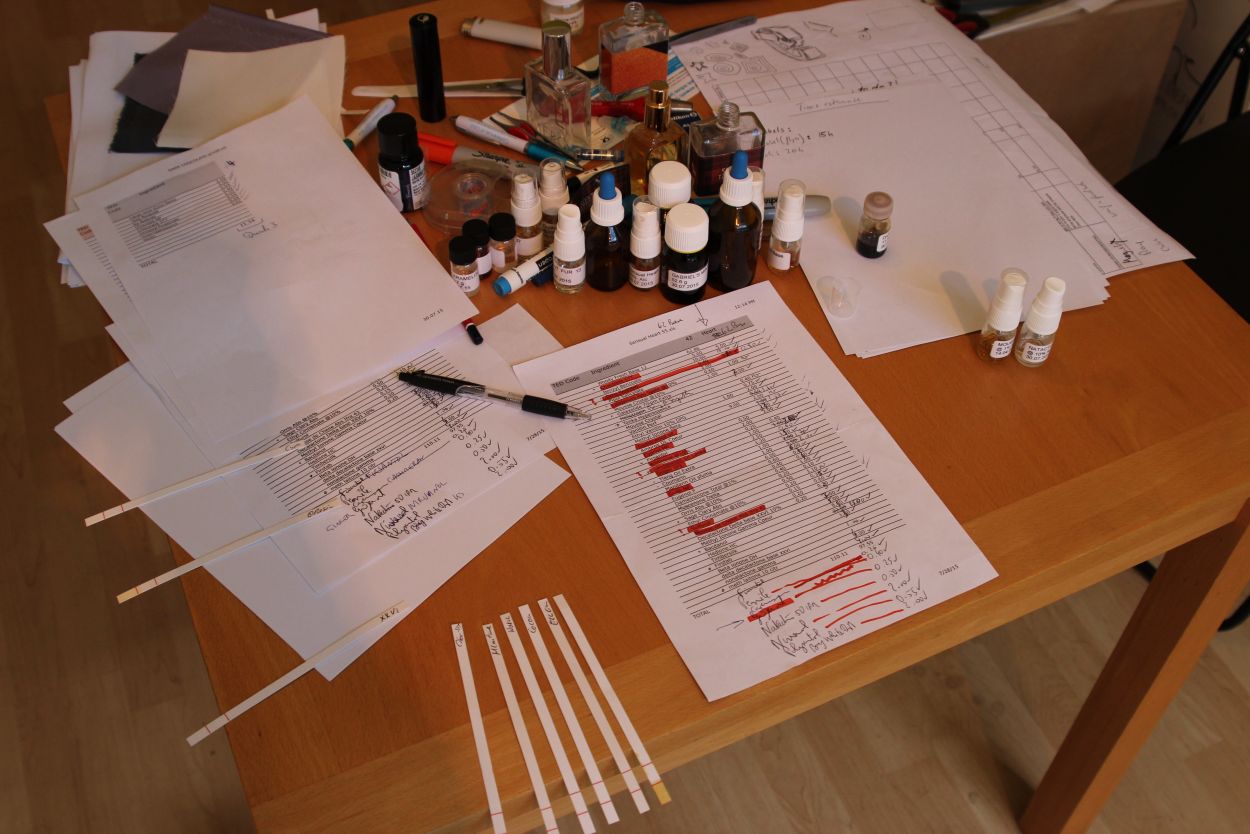

Scents appear ephemeral, volatile, elusive, and transient. Thus, one of the main challenges in the process of scent development is how this seemingly immaterial experience is materialized, that is, how the perfumer moves from first ideas to the final product. At the end of the day one needs to break down the scent into numbers. Along this experimental journey a spreadsheet is used for writing formulae, analyzing modifications and documenting the various stages of the process. A common perfume is composed of odorous materials, using sets of approximately 15 to 80 natural or synthetic ingredients selected from an olfactory palette of approximately 2500 available ingredients. Some of these ingredients are single molecules whereas natural ingredients are combinations of 50-300 molecules themselves. The final product is the result of several dozen smaller experiments that are documented horizontally on the spreadsheet. Vertically, the spreadsheet lists the ingredients used in the experiment. The precise documentation allows the perfumer to go back to an earlier modification if needed. A typical scent development process requires several dozen stages. But we also witnessed extreme cases with several hundred modifications. Have you ever thought that the fleeting experience of a scent boils down to something as prosaic as a spreadsheet?

The power of words1:22

The power of words1:22

Suddenly Christophe discloses the name of an ingredient to the researcher...

The French capucine is commonly known as nasturtium. Its pronunciation in German «Kapuzinerkresse» instantly irritates the perfumer. Hence, the clip reveals factors impacting scent design beyond common textbook wisdom. Even the phonetic sound of an ingredient might make a difference. Christophe’s multisensory approach is perfectly in line with recent scientific findings showing that odor names affect sniffs length, scent familiarity, perception and evaluations. Accordingly, the same scent can be perceived by the same person differently depending on the label attached. Thus, the label «parmesan cheese» positively influences the scent evaluations in comparison with the situation when the scent is labelled as «vomit». Moreover, scent-related words (e.g. strawberry) might be influential for the olfactory experience than non-related words (e.g. old house).

Step by step6:01

Step by step6:01

There is more than meets the eye

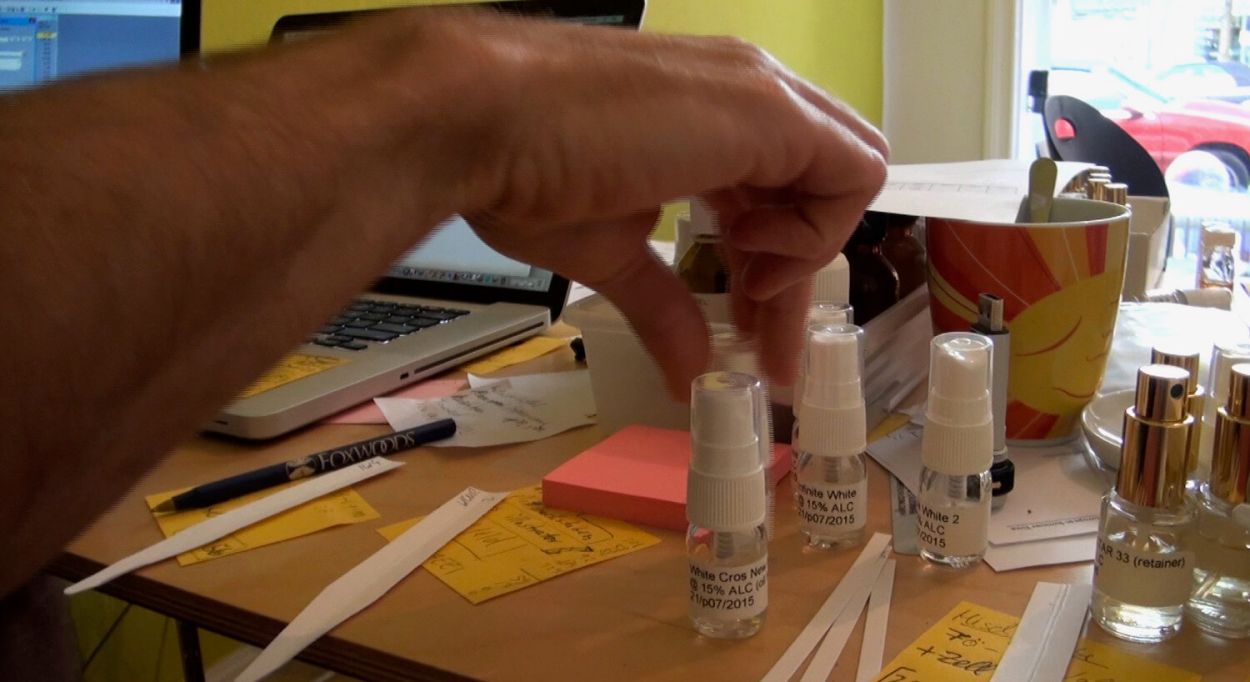

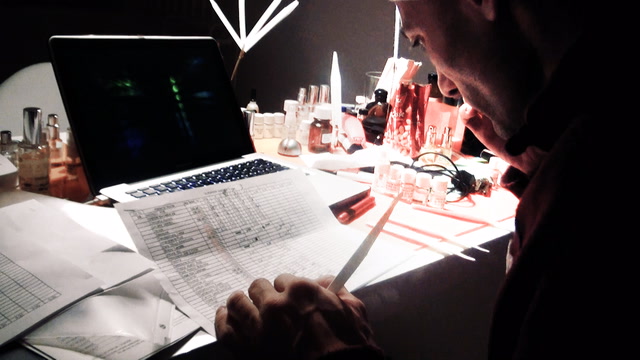

At its core, the practice of perfumery has not changed very much since Renaissance times. The process can be described along a sequence of clearly defined steps: The perfumer starts with some vague ideas which are evoked by certain olfactory ingredients. Thereafter, this rather open process is narrowed down to a precise formula determining the perfume composition in quantitative terms - how much of each material is needed to achieve the ideal balance. Accordingly, the formula is precisely weighed in the laboratory. Each step is accurately documented on a spreadsheet. Using paper strips the perfumer smells and evaluates the scent. Alternative variations are analyzed. The formula is then modified based on detailed analysis. This sequence of steps is repeated until the olfactory experience meets the expectations of the perfumer: Calculating the formula, weighing, evaluating & analyzing.

Nobel laureate Herbert Simon once analyzed how in oil painting every new spot of pigment laid on the canvas creates some kind of pattern that provides a continuing source of new ideas to the painter. Hence, the painting process unfolds as a process of cyclical interaction between the painter and canvas in which current goals lead to new applications of paint, while the gradually changing pattern suggests new goals. In the case of scent development, the cyclical interaction involves the competent use of additional objects (e.g. the formula). However, the practice of perfumery cannot be reduced to this technical dimension. Instead, it is also a meaning and sense-making activity. «To become a perfumer you don’t learn to smell like one – you learn to think like one», Avery Gilbert once noticed. This clip provides a quick primer on this practice.

Wet dog: Chasing the villain5:52

Wet dog: Chasing the villain5:52

This clip features a puzzling mystery Christophe encounters when developing a new scent for Strangelove NYC

In most cases, a perfume is meant to be a pleasurable odor. Technically, it is a mixture of essential oils, aroma compounds, and solvents used to provide an agreeable scent. Yet, the process is more complex than often explained. A useful fragrant ingredient might turn out to be an objectionable odor in a specific combination or concentration: Skatole (from the Greek root skato – meaning «dung») for example, is an indole with a strong fecal odor at high concentrations, but it is often used in perfumery at a much lower concentration where it has a pleasing floral scent. Following the development of a jewel-like fragrance we witnessed how Christophe Laudamiel and Christoph Hornetz suddenly discovered an unpleasant facet, an annoying animalic note. Laudamiel calls it a «wet dog» that only appears after some delay. The two perfumers are puzzled. The phenomenon seems to be really special, if also undesired. They investigate the composition, ingredient by ingredient. In the end, the detective search for malodor delivered a suspect for which Christoph Hornetz had noticed the same unexpected effect in other previous instances: Natactone®. The odor of this chemical compound is often described as «tropical coconut, tonka bean and tobacco». Thus, this clip tells the detective story of a puzzling mystery.

Scent triangle: blotter-nose-formula0:42

Scent triangle: blotter-nose-formula0:42

Fieldnotes are accounts that capture experiences and observations a researcher makes while doing fieldwork.

There is no one «natural», «correct» or even «objective» way for writing fieldnotes. Instead, depending on the researcher’s perception and interpretation, descriptions of the same situation can greatly differ. Yet, some observations are more compelling than others. Given our background in social and organization studies, the field of perfumery was completely new to us. Here is an excerpt from an early fieldnote Claus wrote when following Christophe’s silent practice as shown on this clip:

«The materiality and object-like qualities of scents are really special: on the one hand, the scent appears completely elusive, free of any kind of materiality whatsoever. Indeed, paper strips are necessary in order to make the scent tangible. If not, the scent would literally disappear in thin air, without anyone getting hold of it. Scents are unstable and changing: what smells flowery today, might tip over tomorrow into something fruity. What might appear good on the paper strip can prove unbearable on the skin. Depending on the time and the location, the scent changes its character. In this sense, the scent seems to be missing what usually characterizes an object: A scent is not stable, you can’t take it in your hand and it is usually highly subjective. BUT! The perfumer almost fights with the materiality of the scent: if the raw materials are missing on the shelves, the formula cannot be weighed. Yes indeed, the material proves to be the bottleneck. Even in the largest perfume houses, something is always missing, as Christophe mentioned earlier today. The scent’s materiality thus proves to be the boundary for the perfume development, a boundary that you cannot cross, that you simply have to live with. The materiality of the scent blocks. Scents cannot be recorded and replayed anytime. Scents also cannot be photographed and shown as picture to others. And they certainly cannot be digitalized. But still, one tries to trick the molecules. Because digital formulas are sent around the world as substitutes which outrun the physical logistics. This is what Christophe has done by emailing the formulas for Trust 31, 32, 33 to New York earlier today. But the formula is not a scetch/draft/layout that could be read. Even a perfumer cannot say anything about a scent by just looking at the formula. Instead, what is necessary in order to say something about the scent is the molecule: material, tangible. In this sense, a formula is different from a score. A formula can only be weighed – correctly or erroneously. There is no interpretation. The scent is only conveyable once the formula materializes into molecules. In this respect, a scent cannot be smelled sketchy or poorly. Either you smell the molecules of the weighed formula or you don’t. There is no bad resolution or compression of a scent, no transfer rate and no question of capacity. A scent is all or nothing, present or gone. So only when the formula materializes do we get to know the scent. And only then can we have an exchange about it on the telephone. If Christophe wants to talk to somebody about a scent, he needs to make sure that he himself and the other person he wants to talk to are exposed to the same molecules. When we smell we are taking molecules in. A scent is absorbed, by being incorporated. The scent becomes a part of our body – we inhale it and take it in. In this sense, a smell is something very personal. A scent molecule that I consume cannot be consumed by anyone else. But when you look at a picture, the same picture is also available to me without us being competitors – the same is true for listening/hearing. A bottle without a formula is meaningless. A formula without a bottle is also meaningless. You need blotter, formula and the human nose: A mutually interdependent scent triangle.»

The beauty contest1:50

The beauty contest1:50

Longevity, projection and sillage is not the full story...

Following an experimental approach, the perfumer repeatedly needs to evaluate the results of his formula revisions. This clip zooms in on this specific situation. «This is gorgeous!». Christophe seems to be happy. We witness a deep satisfaction. The evaluation goes beyond longevity, projection and sillage – criteria that are often used to measure the technical performance of a perfume. All this might happen silently under the surface. However, what we see is the creator’s deep affection for his creation, as if he were treating it as an attractive person.

Key quotes with this tag

Images with this tag

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Smelling in another context. Blotters on the table at home.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christoph Hornetz working at his desk at Dreamair in New York.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel getting organized at his desk.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Details on the creative director’s desk: modifications for a new scent.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Still life.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel working on his laptop.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Working through the notes while writing formulas for modifications: This is what Christophe refers to as “creating”.

All Tags

- Affect

- Ambience

- Ambiguity

- Analogy

- Analyzing

- Artifact

- Associating

- Beyond words

- Briefing

- Christophe Laudamiel

- Classifying

- Consuming

- Creating

- Culture

- Deciding

- Embodiment

- Ephemeral

- Ethnography

- Evaluating

- Experimenting

- Hemingway

- Humiecki & Graef

- Industry

- Ingredient

- Interaction

- Labelling

- Laboratory

- Metal

- Modifications

- Mundane work

- Orange Flower

- Paper

- Presenting

- Sense-making

- Shalimar

- Smelling

- Storytelling

- Still life

- Strangelove NYC

- Translating

- Visual

- we are all children

- Words