Family dispute3:18

Family dispute3:18

This video empowers consumers to challenge the salesperson upon their next trip to a perfume store!

At most perfume stores it is common to classify scents by olfactory families. For instance, a department store perfume salesperson identifies the consumer’s passion for a flowery or spicy note and provides more samples from these olfactory families. In encounters such as this, a consumer might easily feel inferior to the salesperson’s expertise. However, in observing the perfume field, we have noticed that even among experts there are highly personal systems of classification that vary from perfumer to perfumer. We asked Christophe Laudamiel and Christoph Hornetz for a set of sample olfactory materials that could help us to better understand some of the everyday practices in the field. One of the perfumers came up with a list of materials grouped by families. One night, we discussed the list over wine and cheese with the two perfumers. On this occasion we learned how even two perfumers who had closely collaborated for several years can quickly disagree about commonly shared olfactory conventions and classifications. Bear in mind that the perfumers talk about single molecules whereas commercial perfumes are composed of several dozen different molecules. After watching the video the viewer should feel empowered to challenge the salesperson upon their next trip to a perfume store!

Revisiting a scent wheel1:57

Revisiting a scent wheel1:57

What you see is what you smell

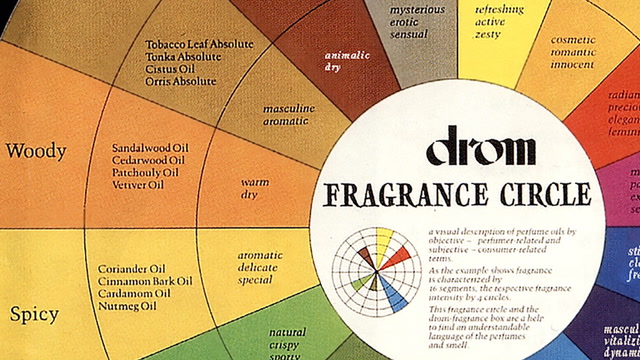

Circles and wheels are common formats used for knowledge visualization in different contexts. The color wheel organizes the relationships between primary, secondary and tertiary colors and visualizes color relationships. In the field of music the circle of fifths visualizes the relationships between major and minor keys. Accordingly, wheels are used to highlight relationships, identify families based on fundamental similarities, and illustrate different grades of intensity. In the olfactory domain, wheels were used in the 16th century to classify the smell of urine for medical purposes. Since the early 20th century the wheel has become a popular format in perfumery. In the world of perfumery the fragrance wheel serves as a handy tool for classifying perfumes. However, many questions are more puzzling than a neat visual design might suggest, as Christophe points out in this clip.

Olfactory discoveries1:18

Olfactory discoveries1:18

Creativity abounds in myths about natural born talents. Yet, it is the doing that makes the difference.

Perfume-making, without a doubt, is a creative practice. However, myths abound about the creative genius as a natural born talent, capable of transforming everything he touches. The limitations of this notion of creativity are increasingly recognized. The blackbox of creativity is opened and little things surface: Practices of creativity! Creative people are open to new experiences and revel in the wonder of the unfamiliar. To paraphrase the Austrian writer Marie von Ebener-Eschenbach: «Wonder does not exist in those incapable of being surprised.» This and many other videos on scentculture.tube show how Christophe allows himself to experience surprise, puzzlement, or confusion in situations he finds uncertain or unique. In this case we see him openly experiencing the wonder that comes with smelling olfactory materials. He subsequently reflects on the phenomena that overtook him, and speculates on how it reshaped his previous understanding of the materials. It appears a culture of surprise is essential for a creative economy.

Wet dog: Chasing the villain5:52

Wet dog: Chasing the villain5:52

This clip features a puzzling mystery Christophe encounters when developing a new scent for Strangelove NYC

In most cases, a perfume is meant to be a pleasurable odor. Technically, it is a mixture of essential oils, aroma compounds, and solvents used to provide an agreeable scent. Yet, the process is more complex than often explained. A useful fragrant ingredient might turn out to be an objectionable odor in a specific combination or concentration: Skatole (from the Greek root skato – meaning «dung») for example, is an indole with a strong fecal odor at high concentrations, but it is often used in perfumery at a much lower concentration where it has a pleasing floral scent. Following the development of a jewel-like fragrance we witnessed how Christophe Laudamiel and Christoph Hornetz suddenly discovered an unpleasant facet, an annoying animalic note. Laudamiel calls it a «wet dog» that only appears after some delay. The two perfumers are puzzled. The phenomenon seems to be really special, if also undesired. They investigate the composition, ingredient by ingredient. In the end, the detective search for malodor delivered a suspect for which Christoph Hornetz had noticed the same unexpected effect in other previous instances: Natactone®. The odor of this chemical compound is often described as «tropical coconut, tonka bean and tobacco». Thus, this clip tells the detective story of a puzzling mystery.

Back to origins1:40

Back to origins1:40

Moving forward can actually imply going back to an earlier version.

In theory, the development process unfolds as incremental steps of improvement. In practice, however, progress is often less clear. This is particularly the case in cultural products that serve an aesthetic, rather than a clearly utilitarian purpose. Standards of quality for creative products derive from abstract ideas rather than clearly defined technical standards and performance features. Creative industries sell identities and experiences. Cultural goods «derive their value from subjective experiences that rely heavily on using symbols in order to manipulate perception and emotion». Consequently, a perfume is increasingly valued for its meaning. «I may like the grapefruit now again», Christophe remarks incidentally in this clip. He had just moved from working with blotters to evaluating selected scent modifications on his skin. Moving forward can actually imply going back to an earlier version.

A naïve child3:37

A naïve child3:37

How does Christophe approach even well known raw materials?

Students often think of learning as an unidirectional accumulation of knowledge. Critical scrutiny, however, reveals that prior knowledge might even hinder efforts to learn or acquire new knowledge: As the British social scientist Gregory Bateson once said: «You can't live without an eraser». Hence, practices of unlearning are essential for all types of knowledge work. In the case of Christophe we often saw him approaching even well known raw materials as if he had never smelled them before. This made us wonder and we asked him about this practice. In fact, there is reason to believe that creative practices hinge upon this kind of open approach.

Encounter with a perfume icon1:05

Encounter with a perfume icon1:05

Shalimar is an iconic perfume. But why is it relevant today?

Successful cultural products blend familiar and novel elements. On the one hand, consumers relate to scents that remind them of others they like. On the other hand, they also appreciate the unexpected pleasure of the new. Depending on the overall position of the scent, the actual relatedness of a perfume can vary from that which is entirely derivative of an existing scent, to that which is clearly building on an existing scent, to that which is predominantly original but shows subtle references to an existing scent. This video captures the moment when a modification reminds Christophe of Shalimar, a great perfume created by Jacques Guerlain in 1921. Its story is part of the wider social and cultural matrix in perfumery. Accordingly, the composition was inspired by Mumtaz Mahal, the wife of Shah Jahal, a 17th century emperor of India. Traditionally, the imitation or matching of an iconic perfume serves as a method of learning the craft. In this situation the sudden connection to Shalimar prompts Christophe to return to the formula. To his surprise, the formula is rather different from Shalimar’s. Yet, the scene documents the remaining influence of an historical icon for cultural production.

The power of words1:22

The power of words1:22

Suddenly Christophe discloses the name of an ingredient to the researcher...

The French capucine is commonly known as nasturtium. Its pronunciation in German «Kapuzinerkresse» instantly irritates the perfumer. Hence, the clip reveals factors impacting scent design beyond common textbook wisdom. Even the phonetic sound of an ingredient might make a difference. Christophe’s multisensory approach is perfectly in line with recent scientific findings showing that odor names affect sniffs length, scent familiarity, perception and evaluations. Accordingly, the same scent can be perceived by the same person differently depending on the label attached. Thus, the label «parmesan cheese» positively influences the scent evaluations in comparison with the situation when the scent is labelled as «vomit». Moreover, scent-related words (e.g. strawberry) might be influential for the olfactory experience than non-related words (e.g. old house).

A conversation with the material3:53

A conversation with the material3:53

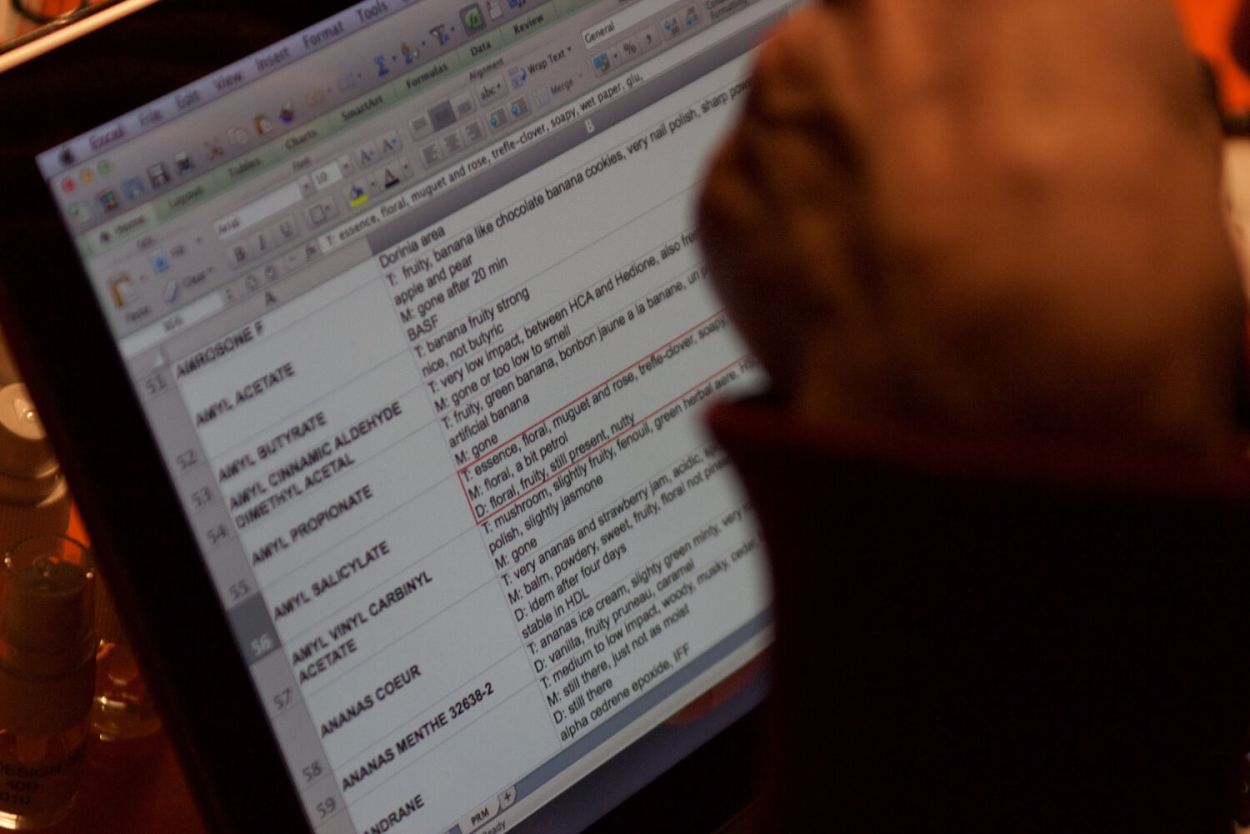

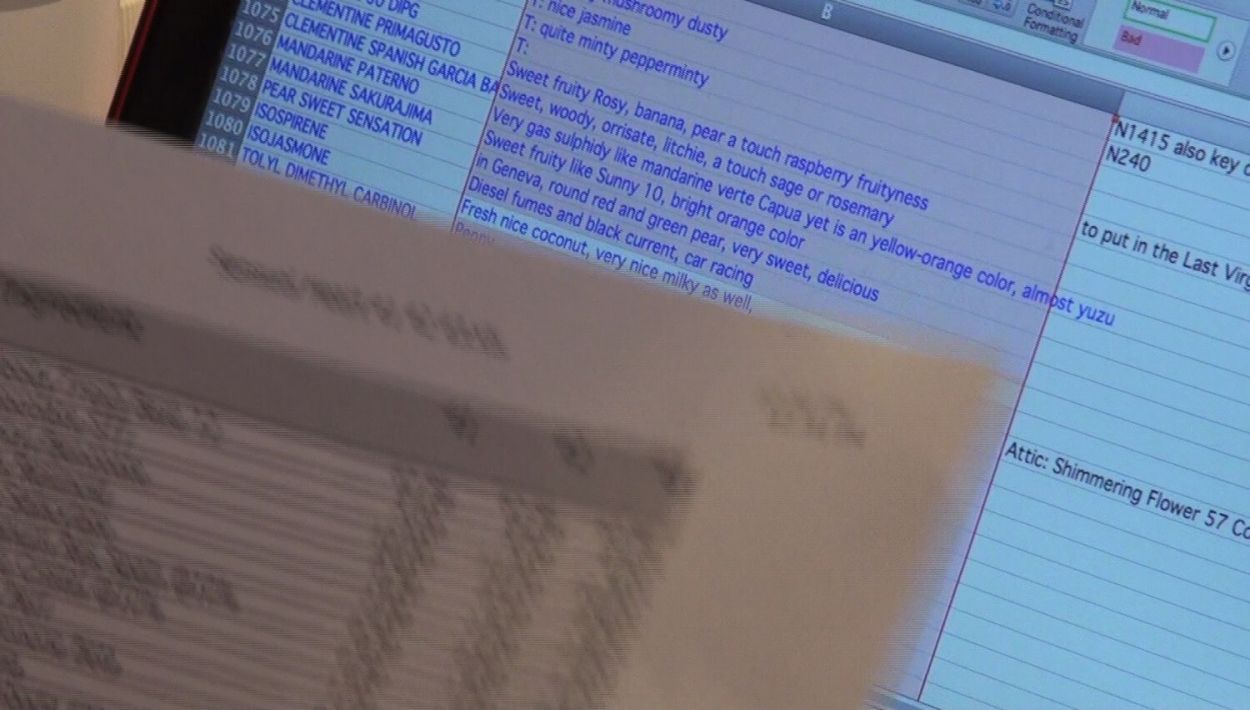

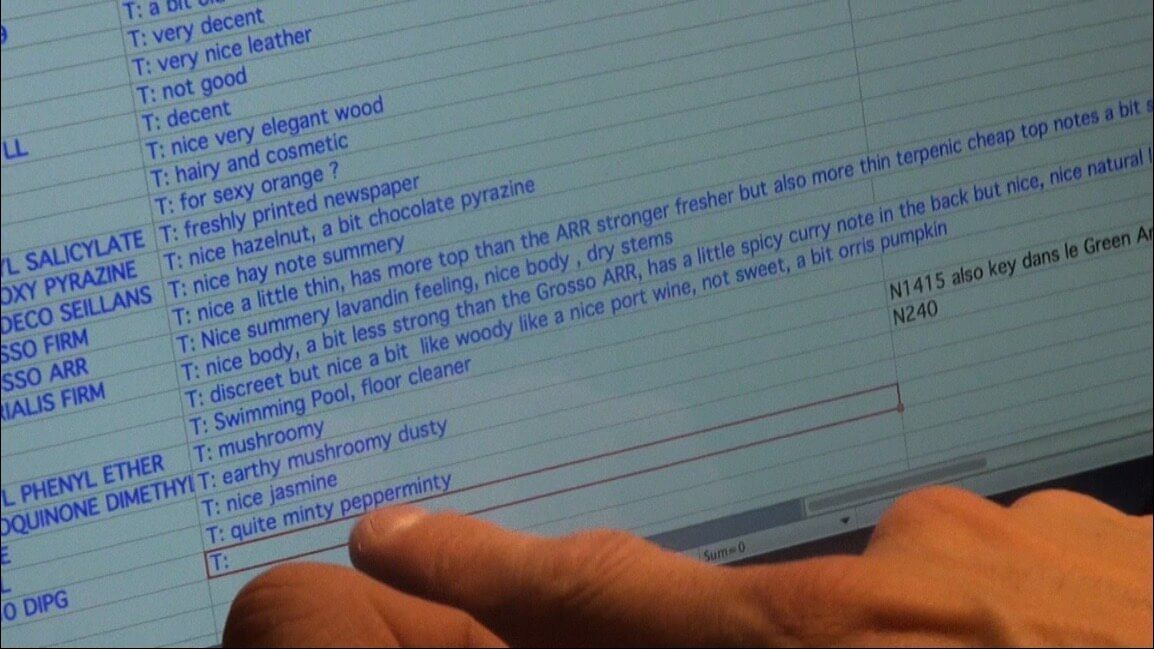

Learning raw materials a perfumery student begins to keep track of associations the smell of these ingredients may trigger.

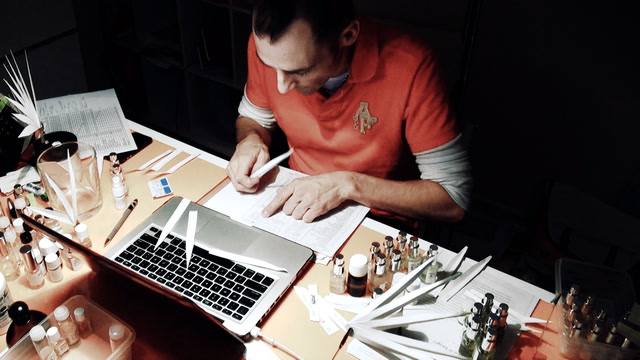

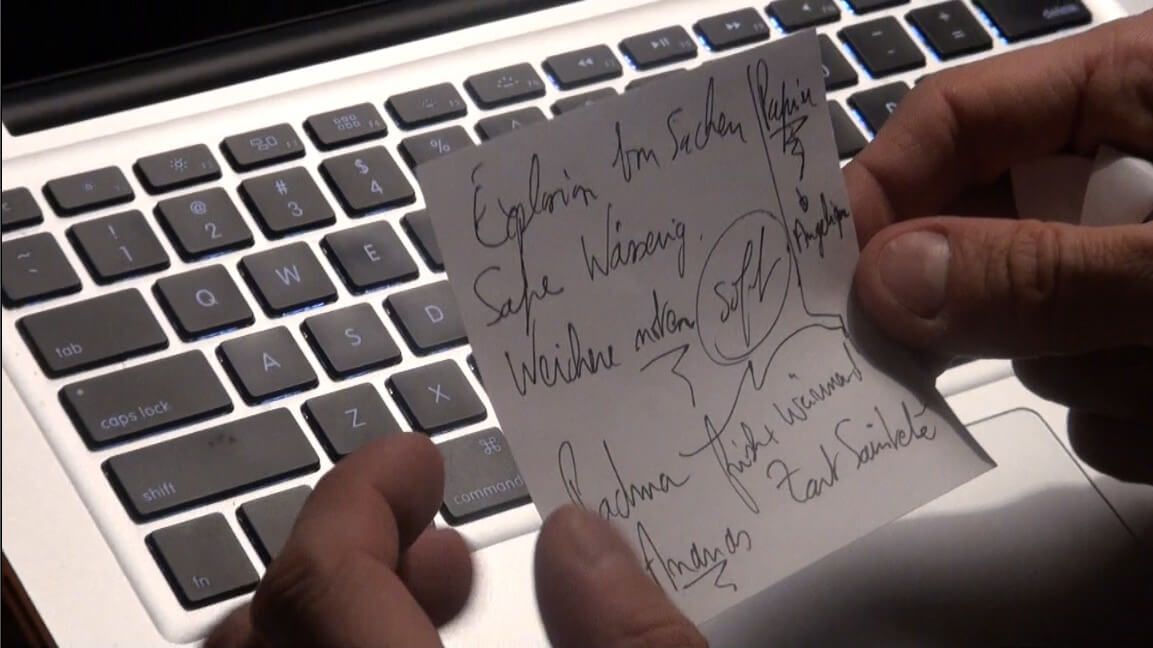

Short entries in a spreadsheet capture descriptive remarks as well as similarities and comparisons between different materials. In this way a perfumer systematically builds up a network of associations that serve various purposes throughout a professional career. In the case of Christophe Laudamie, we often encountered how he maintained his knowledge base and made note of many new surprises by documenting them in his spread sheet. When searching for possible ingredients Christophe searches through the spreadsheet: «Papery» shows up roughly 30 times. Christophe narrows this down to a shortlist of 5-10 ingredients. He then goes to the lab: «Each bottle contains a whole world - a world by itself», Christophe once remarked. This video shows how Christophe explores the worlds of a few bottles and engages in a conversation with the materials on the shelves.

Melt my heart0:50

Melt my heart0:50

We witness a magical moment.

Christophe is putting his left hand on his chest. His eyes express true joy. The perfumer is almost bursting with pleasure while declaring his love for camomille. Christophe recalls the name Elizabeth Ganes, the founder of the high-quality brand StrangeLove NYC mentioned in her briefing: Melt my heart. At the same time the scent affects Christophe emotionally. He cannot control his feelings: Christophe literally embodies the claim: Melt my heart. In many cases a perfumer does not even know the name of the scent when creating. Does this little thing make a difference to the quality of the final composition? Based on this scene one might think so.

Sketching a scent2:19

Sketching a scent2:19

The ephemeral materiality of scent eludes the common conventions of visualizing.

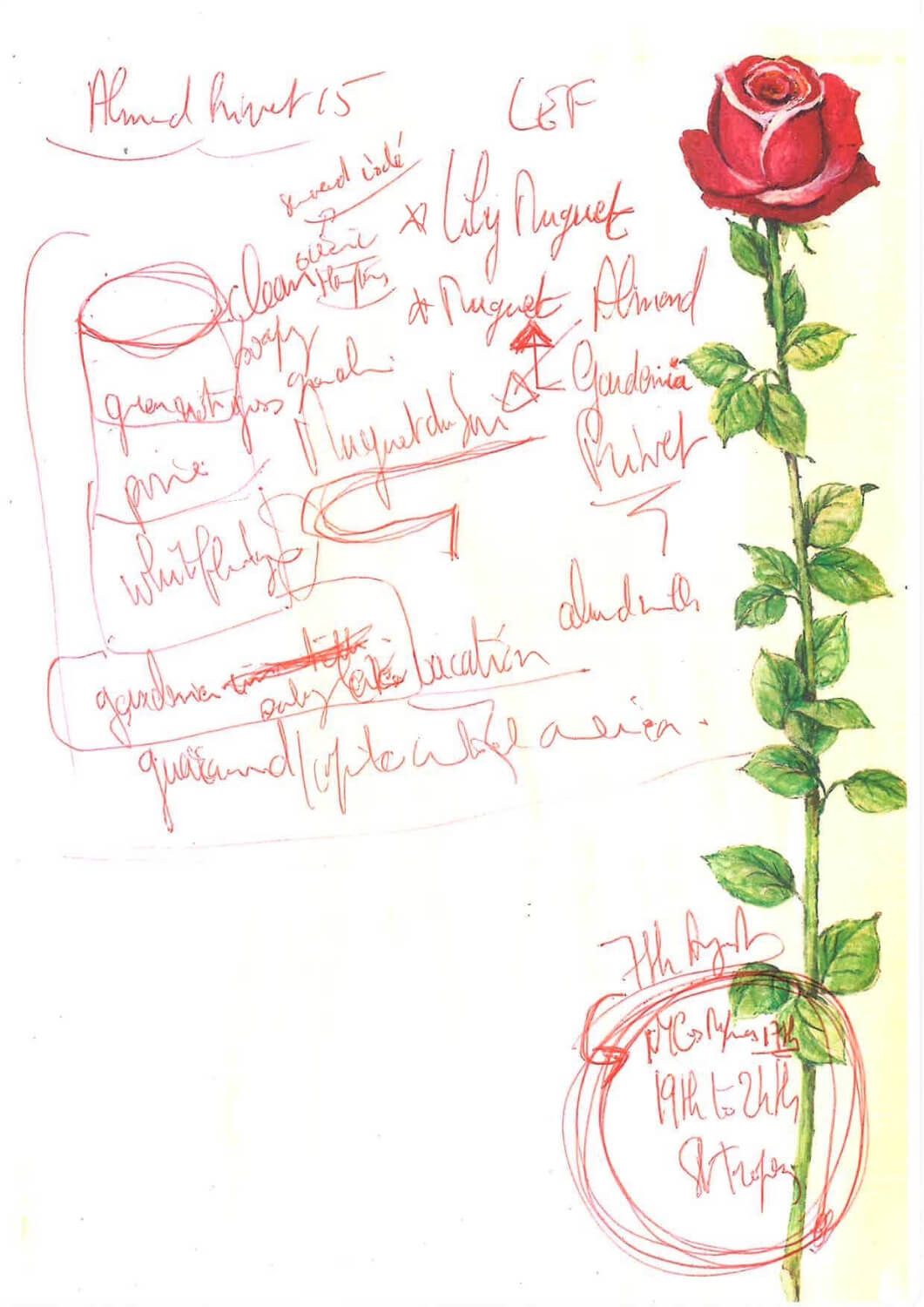

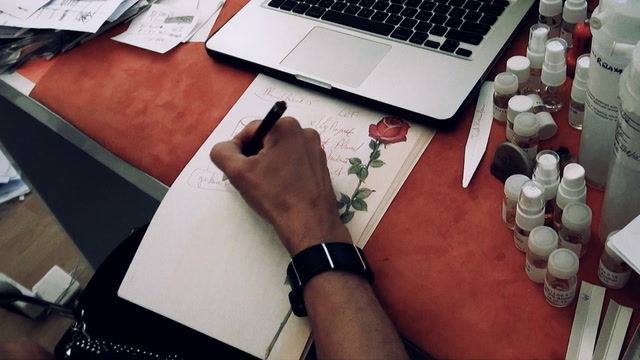

Instead, the qualities inherent to the sense of smell remind us of the limitations of our visual culture: But can scents be rendered visual? Pyramids are widely used forms of visual representation when developing or discussing a fragrance. This clip documents Christophe speaking to a client over the phone. Actually, it is a briefing for a new candle scent. After listening to the client Christophe outlines his ideas. Interestingly, he continuously visualizes his ideas: A scent is drawn. Is this merely an illustration? We doubt it. Since the days of the historical Bauhaus vision has been recognized as a «cognitive power in its own right». The ongoing discourse on visual culture reflects on the visual dimension and its implications for society, culture and business. Thus, the agency of sketches and even the seemingly most banal visual artefacts is increasingly acknowledged. There is more than meets the eye.

Key quotes with this tag

Images with this tag

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Working on a scent brief: making notes. A few moments later the search for papery notes unfolds.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Bottles with ingredients in the laboratory.

Kotomi from flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0

This perfume organ, a common name for the workplace of a perfumer, is exhibited at the Musée International de la Parfumerie in Grasse.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Re-purposing a beverage refrigerator for storing laboratory scents.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

A snapshot of Christhope Laudamiel’s knowledge base.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

A snapshot of Christhope Laudamiel’s knowledge base.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

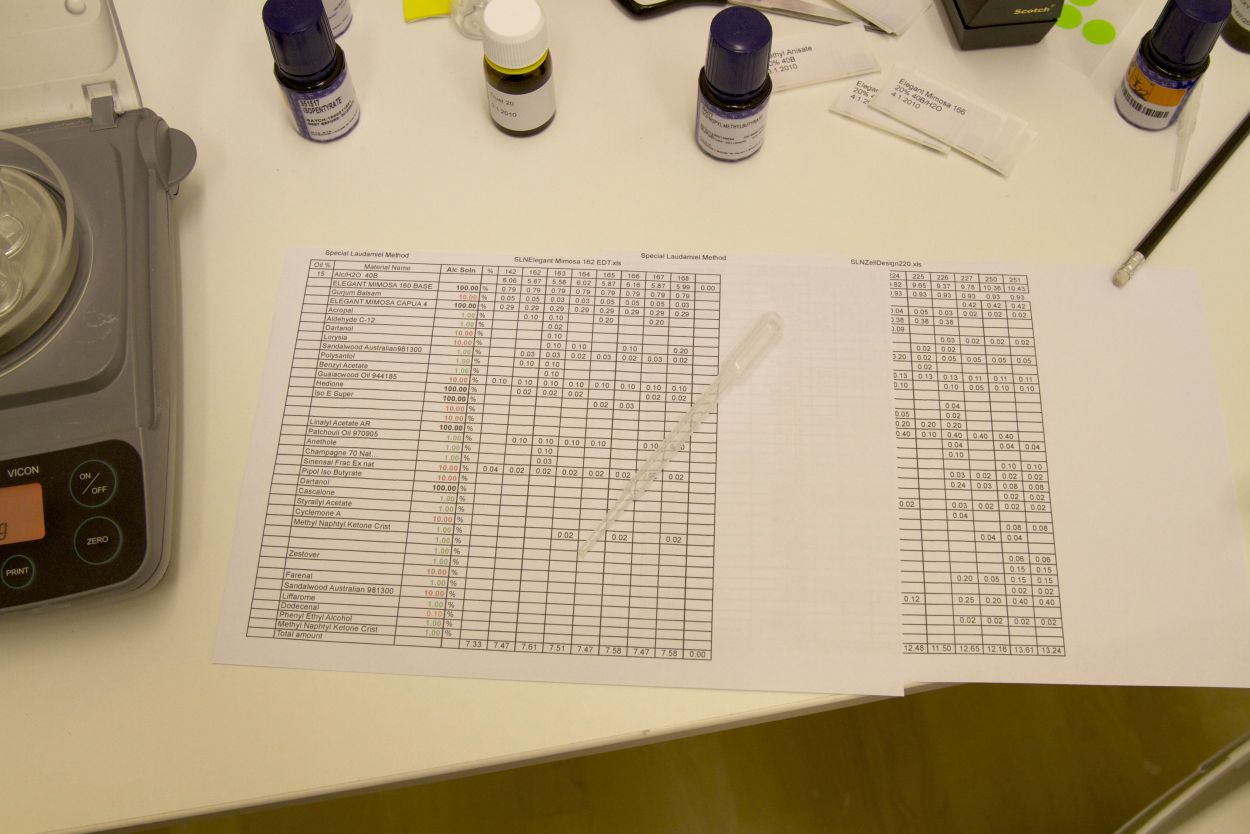

Details in the laboratory: scent ingredients, and a scale.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe consulting his personal knowledge base.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

A box for different variations of orange flower, one of the most expensive ingredients in perfumery, in the laboratory’s fridge.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Details in the laboratory: a spreadsheet, ingredients, and a scale.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Details in the laboratory: a spreadsheet, ingredients, and a scale.

WikiArt Visual Art Encyclopedia, CC-PD-Mark

Roses (also known as The Scent of Roses) by Lilla Cabot Perry.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

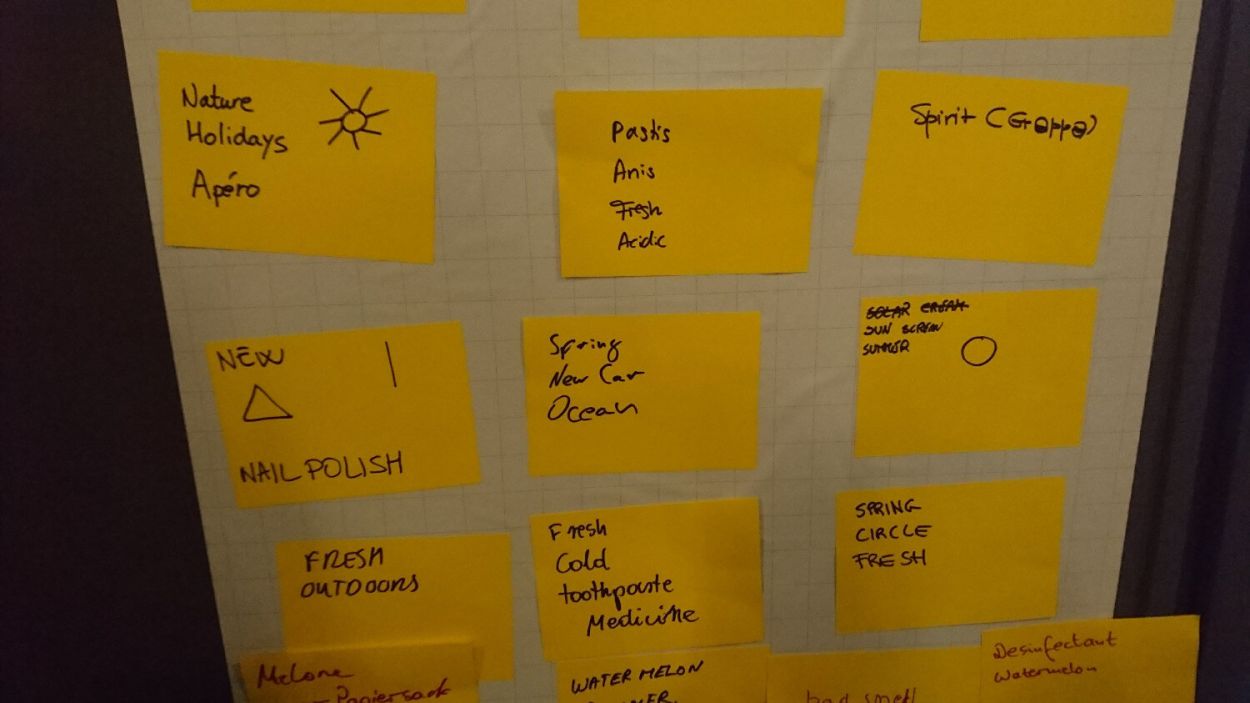

Sharing impressions from smelling the same single molecule ingredient during a workshop.

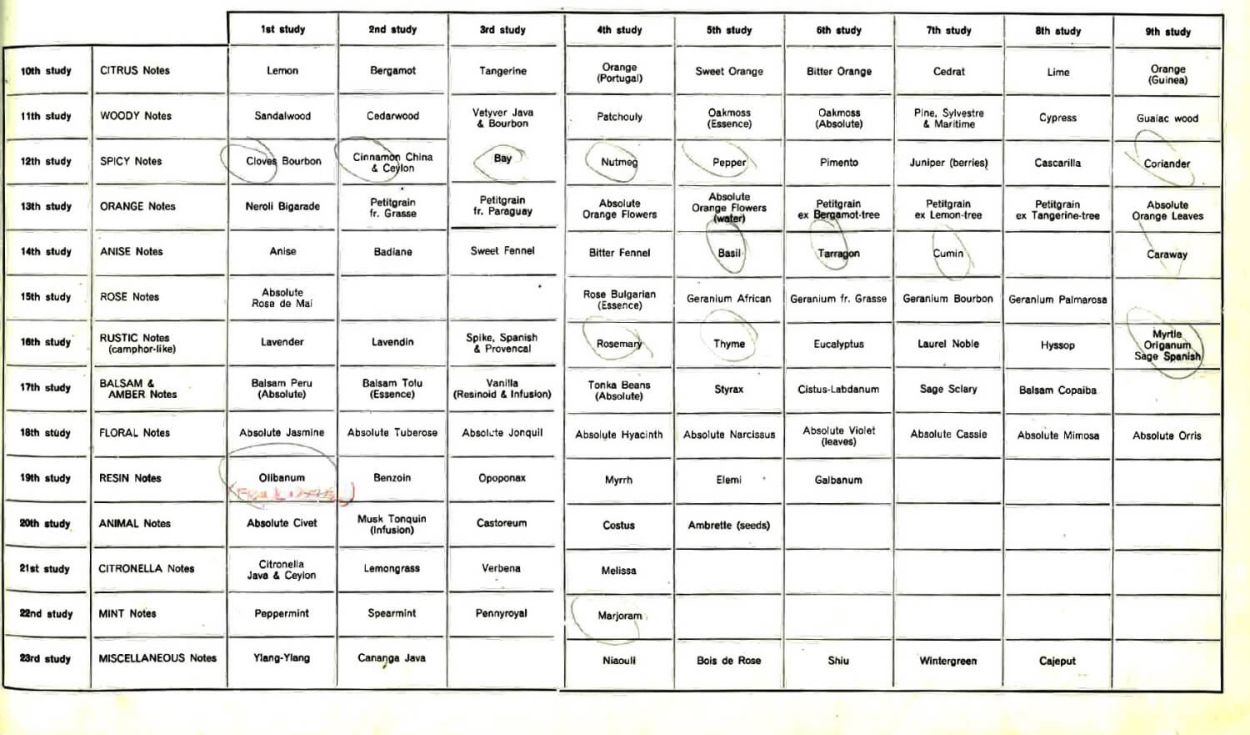

Olfactory study of essential oils and absolutes (Jean Carles method).

Carles, J. (1974). A Method of Creation in Perfumery (As reprinted from Recherches, 1961, 1962, 1963). In W. I. Kaufman (Ed.), Perfume: Photographs and text (pp. 161–180). New York: Dutton, p. 163

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Snapshot of the fridge interior.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

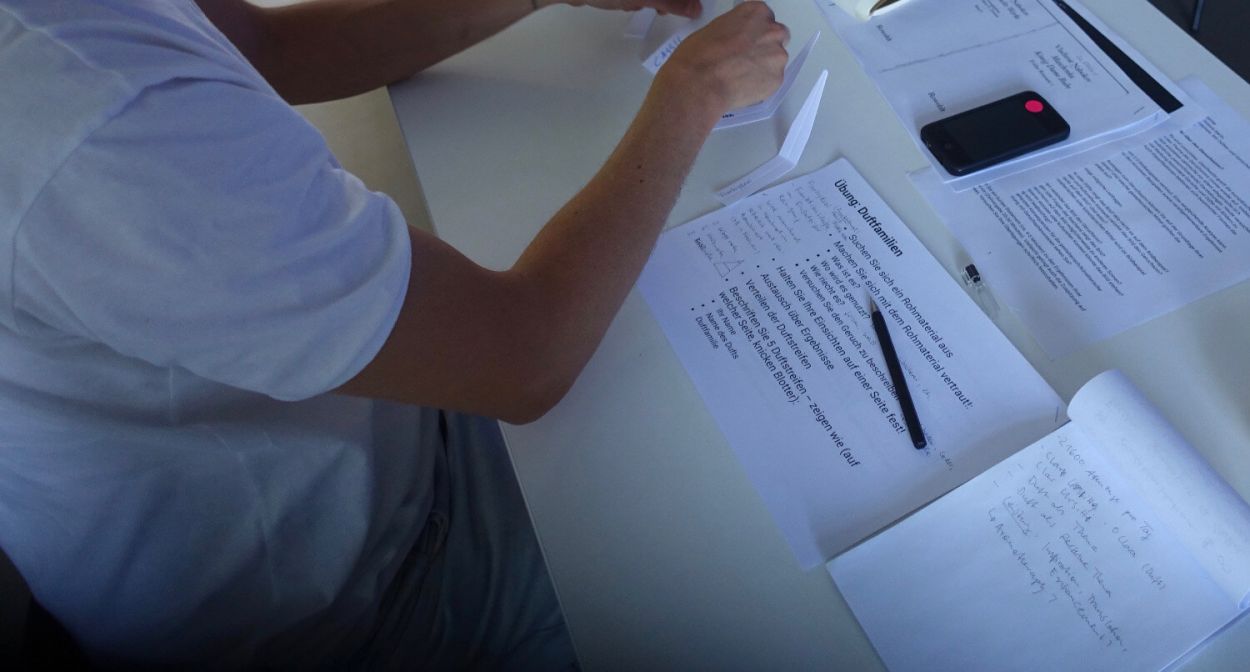

A student familiarizing himself with scent families during a smell culture class at Berlin University of the Arts.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Ingredients (partly in different solutions) alphabetically ordered on the shelf.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christoph Hornetz weighing modifications in the laboratory. Several videos further explore technical practices in the laboratory (e.g. mundane labwork).

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

A few notes inspired by a briefing.

All Tags

- Affect

- Ambience

- Ambiguity

- Analogy

- Analyzing

- Artifact

- Associating

- Beyond words

- Briefing

- Christophe Laudamiel

- Classifying

- Consuming

- Creating

- Culture

- Deciding

- Desk work

- Embodiment

- Ephemeral

- Ethnography

- Evaluating

- Experimenting

- Hemingway

- Humiecki & Graef

- Industry

- Interaction

- Labelling

- Laboratory

- Metal

- Modifications

- Mundane work

- Orange Flower

- Paper

- Presenting

- Sense-making

- Shalimar

- Smelling

- Storytelling

- Still life

- Strangelove NYC

- Translating

- Visual

- we are all children

- Words