The power of words1:22

The power of words1:22

Suddenly Christophe discloses the name of an ingredient to the researcher...

The French capucine is commonly known as nasturtium. Its pronunciation in German «Kapuzinerkresse» instantly irritates the perfumer. Hence, the clip reveals factors impacting scent design beyond common textbook wisdom. Even the phonetic sound of an ingredient might make a difference. Christophe’s multisensory approach is perfectly in line with recent scientific findings showing that odor names affect sniffs length, scent familiarity, perception and evaluations. Accordingly, the same scent can be perceived by the same person differently depending on the label attached. Thus, the label «parmesan cheese» positively influences the scent evaluations in comparison with the situation when the scent is labelled as «vomit». Moreover, scent-related words (e.g. strawberry) might be influential for the olfactory experience than non-related words (e.g. old house).

Scent triangle: blotter-nose-formula0:42

Scent triangle: blotter-nose-formula0:42

Fieldnotes are accounts that capture experiences and observations a researcher makes while doing fieldwork.

There is no one «natural», «correct» or even «objective» way for writing fieldnotes. Instead, depending on the researcher’s perception and interpretation, descriptions of the same situation can greatly differ. Yet, some observations are more compelling than others. Given our background in social and organization studies, the field of perfumery was completely new to us. Here is an excerpt from an early fieldnote Claus wrote when following Christophe’s silent practice as shown on this clip:

«The materiality and object-like qualities of scents are really special: on the one hand, the scent appears completely elusive, free of any kind of materiality whatsoever. Indeed, paper strips are necessary in order to make the scent tangible. If not, the scent would literally disappear in thin air, without anyone getting hold of it. Scents are unstable and changing: what smells flowery today, might tip over tomorrow into something fruity. What might appear good on the paper strip can prove unbearable on the skin. Depending on the time and the location, the scent changes its character. In this sense, the scent seems to be missing what usually characterizes an object: A scent is not stable, you can’t take it in your hand and it is usually highly subjective. BUT! The perfumer almost fights with the materiality of the scent: if the raw materials are missing on the shelves, the formula cannot be weighed. Yes indeed, the material proves to be the bottleneck. Even in the largest perfume houses, something is always missing, as Christophe mentioned earlier today. The scent’s materiality thus proves to be the boundary for the perfume development, a boundary that you cannot cross, that you simply have to live with. The materiality of the scent blocks. Scents cannot be recorded and replayed anytime. Scents also cannot be photographed and shown as picture to others. And they certainly cannot be digitalized. But still, one tries to trick the molecules. Because digital formulas are sent around the world as substitutes which outrun the physical logistics. This is what Christophe has done by emailing the formulas for Trust 31, 32, 33 to New York earlier today. But the formula is not a scetch/draft/layout that could be read. Even a perfumer cannot say anything about a scent by just looking at the formula. Instead, what is necessary in order to say something about the scent is the molecule: material, tangible. In this sense, a formula is different from a score. A formula can only be weighed – correctly or erroneously. There is no interpretation. The scent is only conveyable once the formula materializes into molecules. In this respect, a scent cannot be smelled sketchy or poorly. Either you smell the molecules of the weighed formula or you don’t. There is no bad resolution or compression of a scent, no transfer rate and no question of capacity. A scent is all or nothing, present or gone. So only when the formula materializes do we get to know the scent. And only then can we have an exchange about it on the telephone. If Christophe wants to talk to somebody about a scent, he needs to make sure that he himself and the other person he wants to talk to are exposed to the same molecules. When we smell we are taking molecules in. A scent is absorbed, by being incorporated. The scent becomes a part of our body – we inhale it and take it in. In this sense, a smell is something very personal. A scent molecule that I consume cannot be consumed by anyone else. But when you look at a picture, the same picture is also available to me without us being competitors – the same is true for listening/hearing. A bottle without a formula is meaningless. A formula without a bottle is also meaningless. You need blotter, formula and the human nose: A mutually interdependent scent triangle.»

Olfactory discoveries1:18

Olfactory discoveries1:18

Creativity abounds in myths about natural born talents. Yet, it is the doing that makes the difference.

Perfume-making, without a doubt, is a creative practice. However, myths abound about the creative genius as a natural born talent, capable of transforming everything he touches. The limitations of this notion of creativity are increasingly recognized. The blackbox of creativity is opened and little things surface: Practices of creativity! Creative people are open to new experiences and revel in the wonder of the unfamiliar. To paraphrase the Austrian writer Marie von Ebener-Eschenbach: «Wonder does not exist in those incapable of being surprised.» This and many other videos on scentculture.tube show how Christophe allows himself to experience surprise, puzzlement, or confusion in situations he finds uncertain or unique. In this case we see him openly experiencing the wonder that comes with smelling olfactory materials. He subsequently reflects on the phenomena that overtook him, and speculates on how it reshaped his previous understanding of the materials. It appears a culture of surprise is essential for a creative economy.

Wet dog: Chasing the villain5:52

Wet dog: Chasing the villain5:52

This clip features a puzzling mystery Christophe encounters when developing a new scent for Strangelove NYC

In most cases, a perfume is meant to be a pleasurable odor. Technically, it is a mixture of essential oils, aroma compounds, and solvents used to provide an agreeable scent. Yet, the process is more complex than often explained. A useful fragrant ingredient might turn out to be an objectionable odor in a specific combination or concentration: Skatole (from the Greek root skato – meaning «dung») for example, is an indole with a strong fecal odor at high concentrations, but it is often used in perfumery at a much lower concentration where it has a pleasing floral scent. Following the development of a jewel-like fragrance we witnessed how Christophe Laudamiel and Christoph Hornetz suddenly discovered an unpleasant facet, an annoying animalic note. Laudamiel calls it a «wet dog» that only appears after some delay. The two perfumers are puzzled. The phenomenon seems to be really special, if also undesired. They investigate the composition, ingredient by ingredient. In the end, the detective search for malodor delivered a suspect for which Christoph Hornetz had noticed the same unexpected effect in other previous instances: Natactone®. The odor of this chemical compound is often described as «tropical coconut, tonka bean and tobacco». Thus, this clip tells the detective story of a puzzling mystery.

Beyond words1:43

Beyond words1:43

Bodily ways of knowing help Christophe go beyond the limitations of an individual creator.

Christophe Laudamiel once described a perfumer as someone «who masters the behaviour and the perception of volatile molecules by the nose and the brain». Accordingly, a perfumer definitely knows how to create a perfume. Yet, this clip reveals the limitations of an individual creator. Practices of collective smelling and sense-making are needed to challenge and confirm the creative path. In this respect a scent development project serves as an extreme case: Verbal utterances account only for a small fraction of human communication. In addition, body language & posture, silence, gestures and face grimaces function as nonverbal feedback. At first sight, this clip might seem boring because there is not very much happening. At a deeper level however, one can notice the deep uncertainties a creator bears. Experiencing scents, sensing, and sense-making emerge mutually in active and reflective practices that have to cope with the paucity of language to describe scents and engage with bodily ways of knowing.

Back to origins1:40

Back to origins1:40

Moving forward can actually imply going back to an earlier version.

In theory, the development process unfolds as incremental steps of improvement. In practice, however, progress is often less clear. This is particularly the case in cultural products that serve an aesthetic, rather than a clearly utilitarian purpose. Standards of quality for creative products derive from abstract ideas rather than clearly defined technical standards and performance features. Creative industries sell identities and experiences. Cultural goods «derive their value from subjective experiences that rely heavily on using symbols in order to manipulate perception and emotion». Consequently, a perfume is increasingly valued for its meaning. «I may like the grapefruit now again», Christophe remarks incidentally in this clip. He had just moved from working with blotters to evaluating selected scent modifications on his skin. Moving forward can actually imply going back to an earlier version.

A naïve child3:37

A naïve child3:37

How does Christophe approach even well known raw materials?

Students often think of learning as an unidirectional accumulation of knowledge. Critical scrutiny, however, reveals that prior knowledge might even hinder efforts to learn or acquire new knowledge: As the British social scientist Gregory Bateson once said: «You can't live without an eraser». Hence, practices of unlearning are essential for all types of knowledge work. In the case of Christophe we often saw him approaching even well known raw materials as if he had never smelled them before. This made us wonder and we asked him about this practice. In fact, there is reason to believe that creative practices hinge upon this kind of open approach.

Step by step6:01

Step by step6:01

There is more than meets the eye

At its core, the practice of perfumery has not changed very much since Renaissance times. The process can be described along a sequence of clearly defined steps: The perfumer starts with some vague ideas which are evoked by certain olfactory ingredients. Thereafter, this rather open process is narrowed down to a precise formula determining the perfume composition in quantitative terms - how much of each material is needed to achieve the ideal balance. Accordingly, the formula is precisely weighed in the laboratory. Each step is accurately documented on a spreadsheet. Using paper strips the perfumer smells and evaluates the scent. Alternative variations are analyzed. The formula is then modified based on detailed analysis. This sequence of steps is repeated until the olfactory experience meets the expectations of the perfumer: Calculating the formula, weighing, evaluating & analyzing.

Nobel laureate Herbert Simon once analyzed how in oil painting every new spot of pigment laid on the canvas creates some kind of pattern that provides a continuing source of new ideas to the painter. Hence, the painting process unfolds as a process of cyclical interaction between the painter and canvas in which current goals lead to new applications of paint, while the gradually changing pattern suggests new goals. In the case of scent development, the cyclical interaction involves the competent use of additional objects (e.g. the formula). However, the practice of perfumery cannot be reduced to this technical dimension. Instead, it is also a meaning and sense-making activity. «To become a perfumer you don’t learn to smell like one – you learn to think like one», Avery Gilbert once noticed. This clip provides a quick primer on this practice.

Taking perfumes to nightlife0:57

Taking perfumes to nightlife0:57

The ephemeral materiality of scent deeply impacts on how a perfumer can balance life and work. The perfumer’s body is a resource as well as a constraint.

Moving from paper testing strips to the skin can drastically change the overall experience of a perfume. What might be banal everyday knowledge has far reaching consequences for a professional perfumer. The skin of a perfumer is a constraint in the process because there are hardly more than three spots on each arm to spray. Once sprayed on the arm the scent will stay until it has completely evaporated. How long this takes is a matter of the scent’s molecular structure. Hence, a scent does not comply with an organization’s time regime. Instead, the involvement of the perfumer’s body makes the perfumer take his work home, or in this case, to the bar. In this clip, set in a bar late at night, Christophe notices a few molecules on his arm, and casually evaluates the set of recent creations. The undisciplined nature of scent blurs the boundaries of work and non-work.

Fragrant upcycling2:56

Fragrant upcycling2:56

Garbage smells.

Anyone with a nose knows that trash can stink. It is this truism of modern life that this clip challenges: Trash can smell nice. According to our fieldnotes Christophe casually once remarked: «The garbage often smells good. And: If you want to remake it, good luck». Hence, smelling trash is a recurring theme in a perfumer’s studio. This clip, however, shows how smelling a perfumer’s trash bin can open a discussion on sustainability in the fragrance industry and envision a future of fragrant upcycling.

bodywork0:44

bodywork0:44

subject/object, real/representational, people/things, mind/body, form/substance, body/soul etc.

Modernity has often been characterised in terms of its operation of dualisms. Over the past few decades the social sciences have witnessed an increasing interest in the body and analyzed embodied aspects of action, social interaction and meaning-making. This clip draws attention to the perfumer’s body as an active player in the process. Bodily practices are shown as a potential resource to produce value: Labour exists as «a resource in the bodiliness of the worker», Karl Marx once noticed in his influential value theory. Scents actually penetrate and involve the human body. However, once a scent becomes part of olfaction, its status as object is completely lost in the body and in the experience of olfaction The perfumer’s body serves as the origin point for all olfactory knowledge and experience. It is the basic source of information and comprehension that gives rise to brief intuitive observations. These observations are often articulated by the perfumer using surprisingly emotional, experiential and sensorial vocabulary. In fact, we seldom heard perfumers use the technical vocabulary we anticipated based on our preparatory readings. The role of the body in perfumery is certainly an extreme case. Yet, a deeper understanding of this practice helps to traverse modernity’s dualisms.

Mundane lab work4:00

Mundane lab work4:00

Perfumery is not always glamorous. Creativity unfolds in a nexus of mundane work practices.

Perfumery is practiced in a lab. The lab serves several functions. It is a storage space for the ingredients that are alphabetically shelved. More sensitive materials are kept in a designated refrigerator in the lab. Moreover, the lab provides specific tools and equipment (e.g. scientific scales). As a special workplace the lab is the place for creating solutions of solid materials or weighing formulae. The lab also serves as the perfumer’s archive where modifications of completed projects are stored. All in all, the lab provides access to the world of the volatile molecules. While observing Christophe’s creative process we were surprised how often he went to the lab to reconnect to his material base.

Leading Perfumery schools often expect a formal education in chemistry. For example, Christophe Laudamiel studied chemistry in France and eventually earned a Masters degree from MIT. Nevertheless there are other eminent perfumers who never studied chemistry: Francois Coty, Ernest Beaux, and Jean Carles, to name three titans of perfumery. Thus, the relevance of a formal education is certainly debatable. But there is no doubt that a profound understanding of chemical compounds, how they behave or react with each other is essential. At the end of the day the scent development process must follow scientific practices and comply with technical standards and procedures. Hence, this clip zooms into the mundane, less spectacular aspects of lab work. The current discussion of design thinking often reduces design practice to an immaterial, intellectual problem solving technique. In this one-sided context, a closer look at mundane lab work put renewed emphasis back into material practice.

A conversation with the material3:53

A conversation with the material3:53

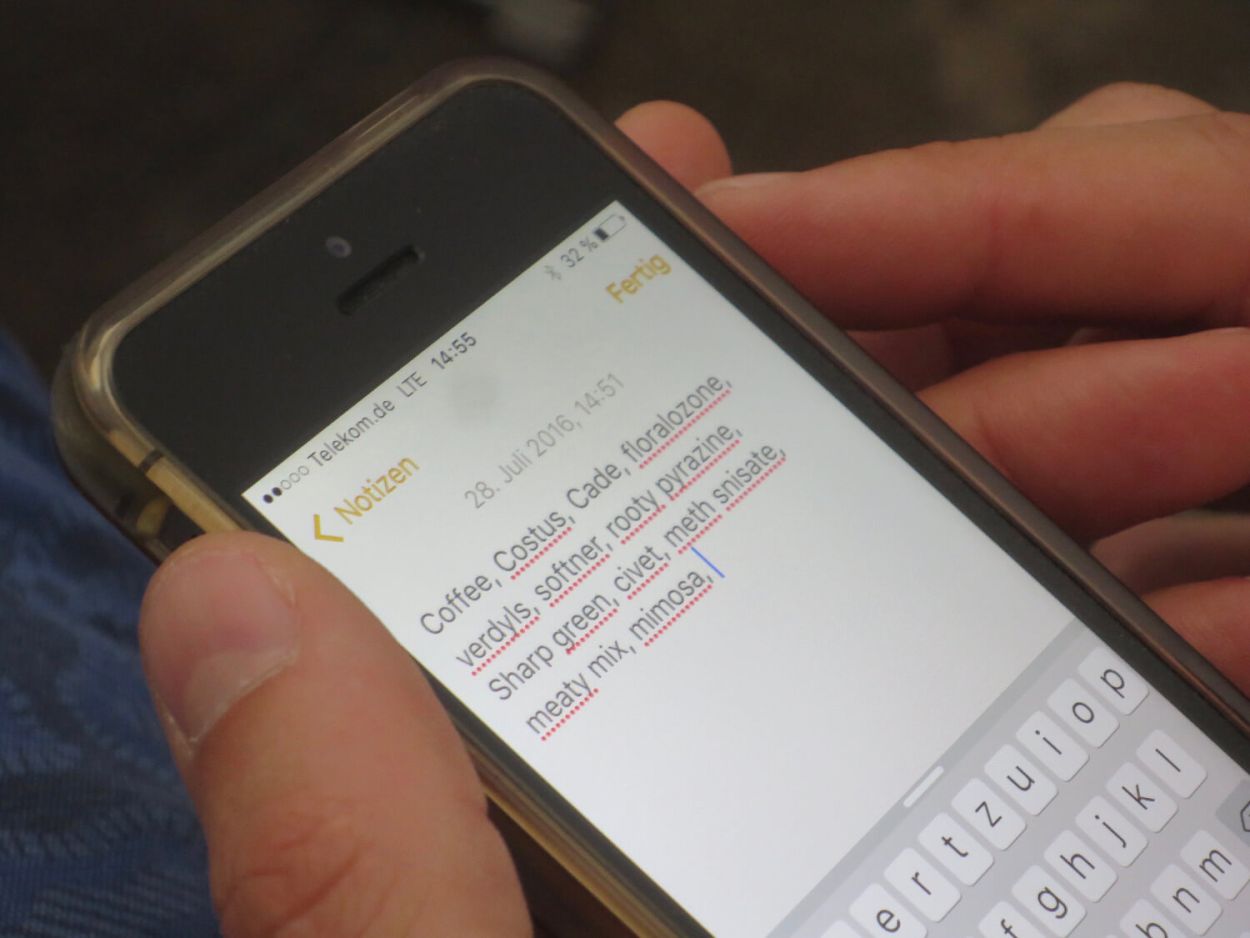

Learning raw materials a perfumery student begins to keep track of associations the smell of these ingredients may trigger.

Short entries in a spreadsheet capture descriptive remarks as well as similarities and comparisons between different materials. In this way a perfumer systematically builds up a network of associations that serve various purposes throughout a professional career. In the case of Christophe Laudamie, we often encountered how he maintained his knowledge base and made note of many new surprises by documenting them in his spread sheet. When searching for possible ingredients Christophe searches through the spreadsheet: «Papery» shows up roughly 30 times. Christophe narrows this down to a shortlist of 5-10 ingredients. He then goes to the lab: «Each bottle contains a whole world - a world by itself», Christophe once remarked. This video shows how Christophe explores the worlds of a few bottles and engages in a conversation with the materials on the shelves.

Evaluative moments2:33

Evaluative moments2:33

Three professionals engage in smelling and discussing an advanced modification of Meltmyheart, a fragrance by StrangeLove NYC.

We see how Christophe Laudamiel, Christoph Hornetz and the flavorist Marlene Staiger spontaneously share their impressions and associations. Apparently, there is no one way of evaluating a scent. A closer look reveals how micro-practices of smelling and using blotters can differ. Christophe is particularly interested how the other two experience a certain effect that he describes as «hot metal effect». The subtitles show how the three professionals cannot agree on what the dominant note of this scent smells like: caramel, coconut and hot metal stand next to each other. A shared interpretation of what they are actually smelling seems to be rather unimportant. Yet, something is achieved in this communication. It is neither explicit agreement nor disagreement. Instead it is the affective experience the three professionals express and collectively interpret as «good». And it is this affective experience that might be key to understanding how organizing is accomplished in a creative context. Is it possible that affects really constitute an organization?

The beauty contest1:50

The beauty contest1:50

Longevity, projection and sillage is not the full story...

Following an experimental approach, the perfumer repeatedly needs to evaluate the results of his formula revisions. This clip zooms in on this specific situation. «This is gorgeous!». Christophe seems to be happy. We witness a deep satisfaction. The evaluation goes beyond longevity, projection and sillage – criteria that are often used to measure the technical performance of a perfume. All this might happen silently under the surface. However, what we see is the creator’s deep affection for his creation, as if he were treating it as an attractive person.

No one can smell pepper1:21

No one can smell pepper1:21

Modification by modification Christophe seeks a numerical feedback on digital scent technology project.

In an increasingly digital world the proximate senses of smell, touch and taste stand out. One cannot capture a smell and send it like a photo via email or other digital communication service. At least not yet. Nevertheless digital scent technology is a vibrant field attracting smart minds all over the world. As a perfumer, Christophe Laudamiel has been involved with some cutting edge projects from the very beginning.

During our observations Christophe developed some realistic scents (e.g. pepper, croissant; French bread etc.) that could work with some innovative digital scent transmission applications. In fact, it was a surprise to see how much the technology of the application can be a challenge to the design of a fragrance. Thus, the choice of a raisin as a carrier material can have a huge impact on the formula. In this case the evaluation followed a more systematic procedure as this clip shows: How precisely does this modification capture the desired scent? In other words: Is this really pepper? And how strong is the scent within the application? In other words: How strong is the pepper? Modification by modification Christophe Laudamiel seeks Christoph Hornetz’s numerical feedback on both questions.

(De)briefing a scent2:36

(De)briefing a scent2:36

What is challenging about talking about scents? Can scents have structure? How many dimensions does a scent have?

A meeting with Sebastian Fischenich, the creative director of Humiecki & Graef, provides an opportunity to reflect on the state of the project. The perfumer presents alternative modifications and clarifies next steps with the creative director. In this case the two evaluate alternative scent «structures,» an initially surprising metaphor used to capture the fleeting nature of the olfactory experience.

Key quotes with this tag

Images with this tag

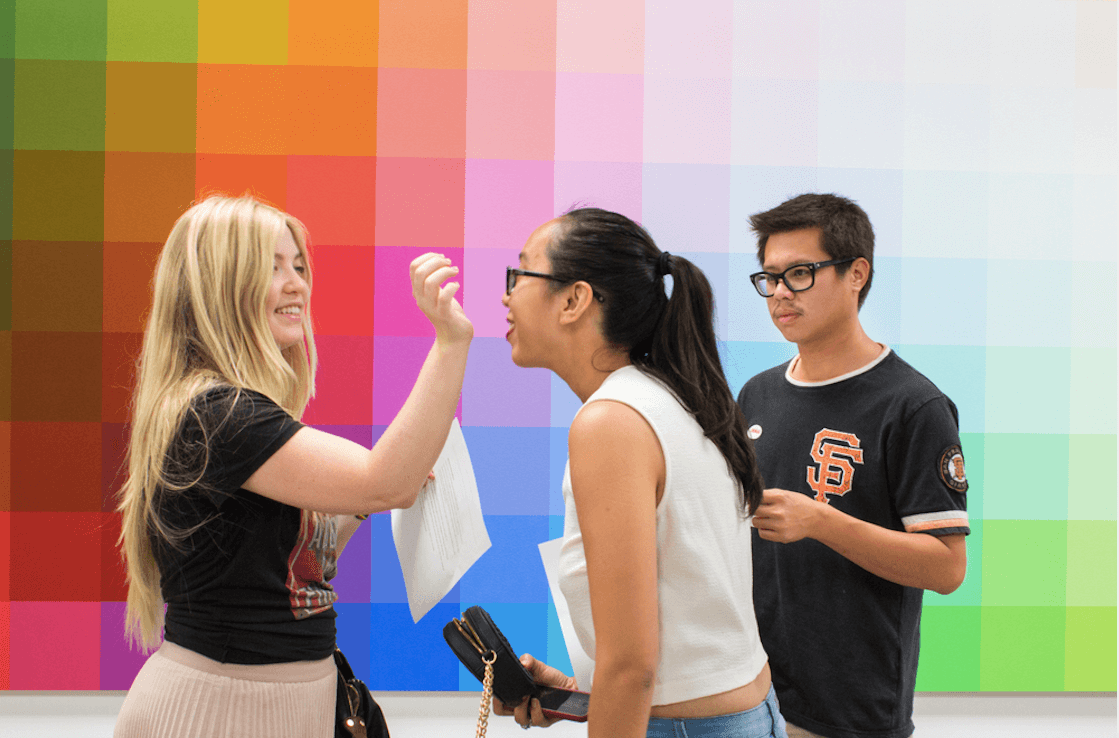

Courtesy: Brian Goeltzenleuchter: Patron Demographic Profile 2016.

Visitors experiencing Sillage, an olfactory artwork by Brian Goeltzenleuchter, at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

From Wikimedia Commons

Religious life has given rise to a multi-faceted, vivid scent culture. Zdzisław Jasiński (1891): Palm Sunday mass.

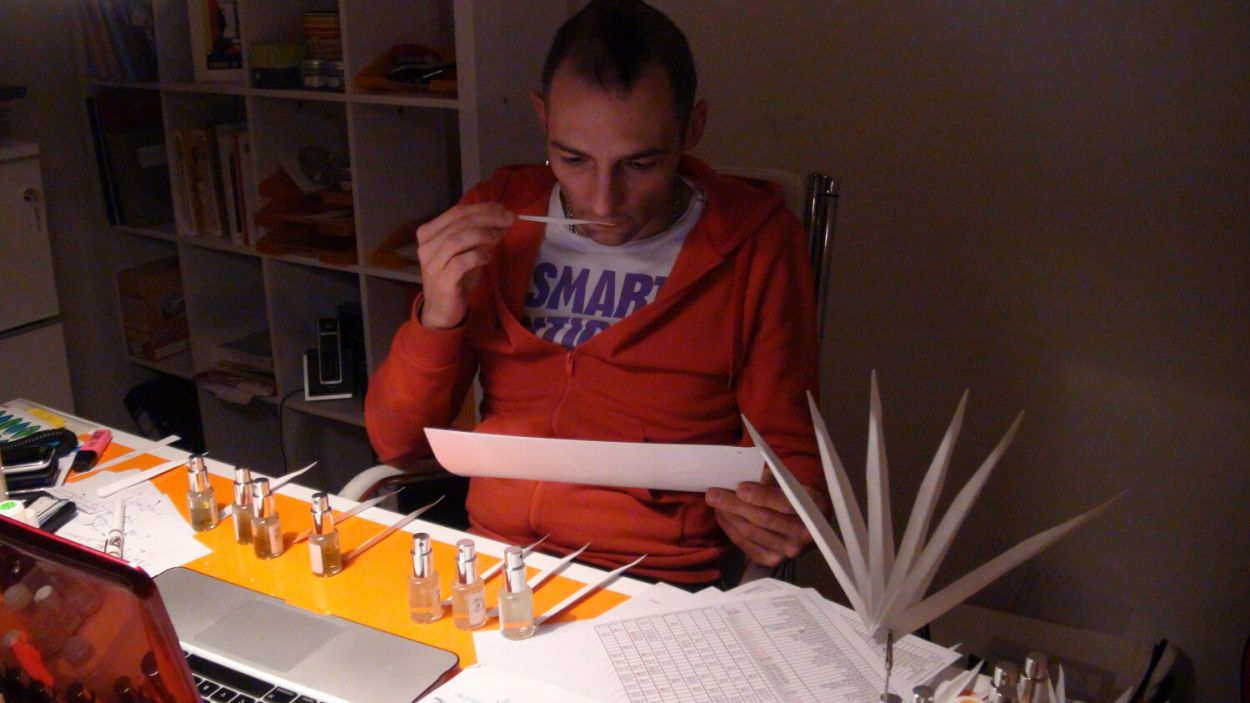

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

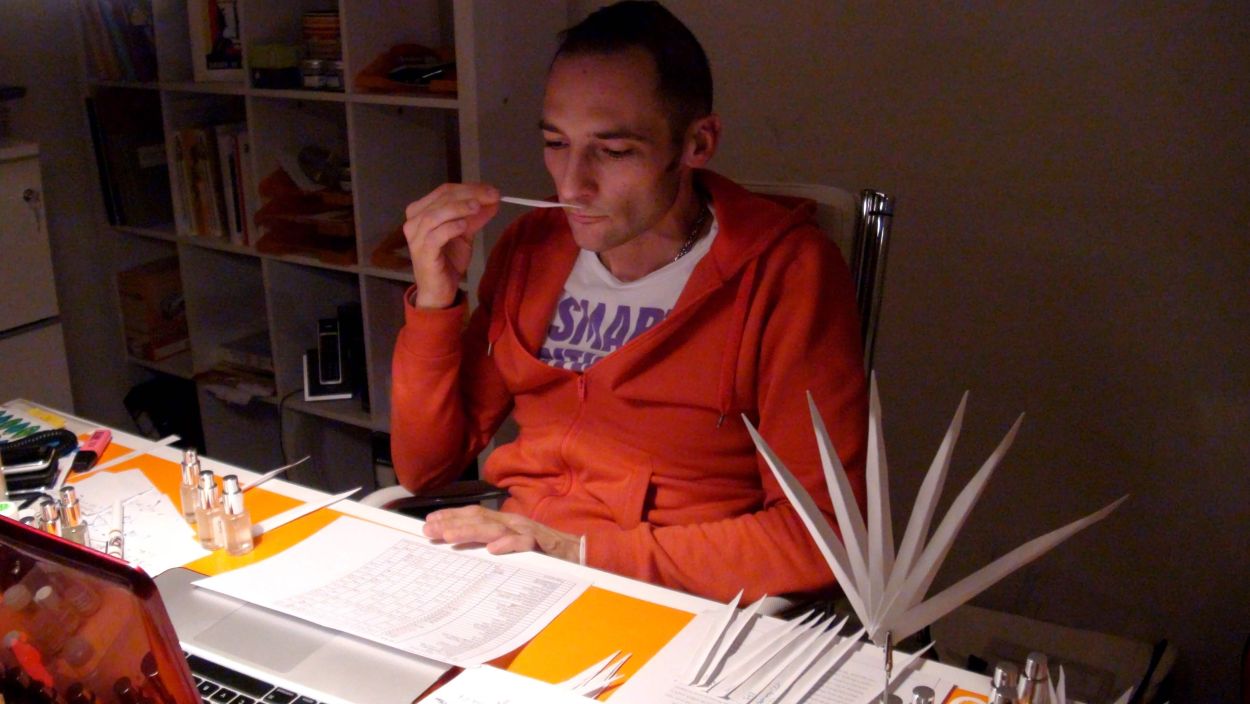

Christophe Laudamiel smelling multiple scent accords.

«Poor human olfaction is a 19th-century myth», headlined one of the top scientific journals in 2017. This headline underscores a cultural and academic reassessment of the sense of smell. This single indication can be complemented by numerous other sources. Accordingly, the human sense of smell is more advanced and more relevant than many believe. Science 356, 597 (2017) 12 May 2017

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

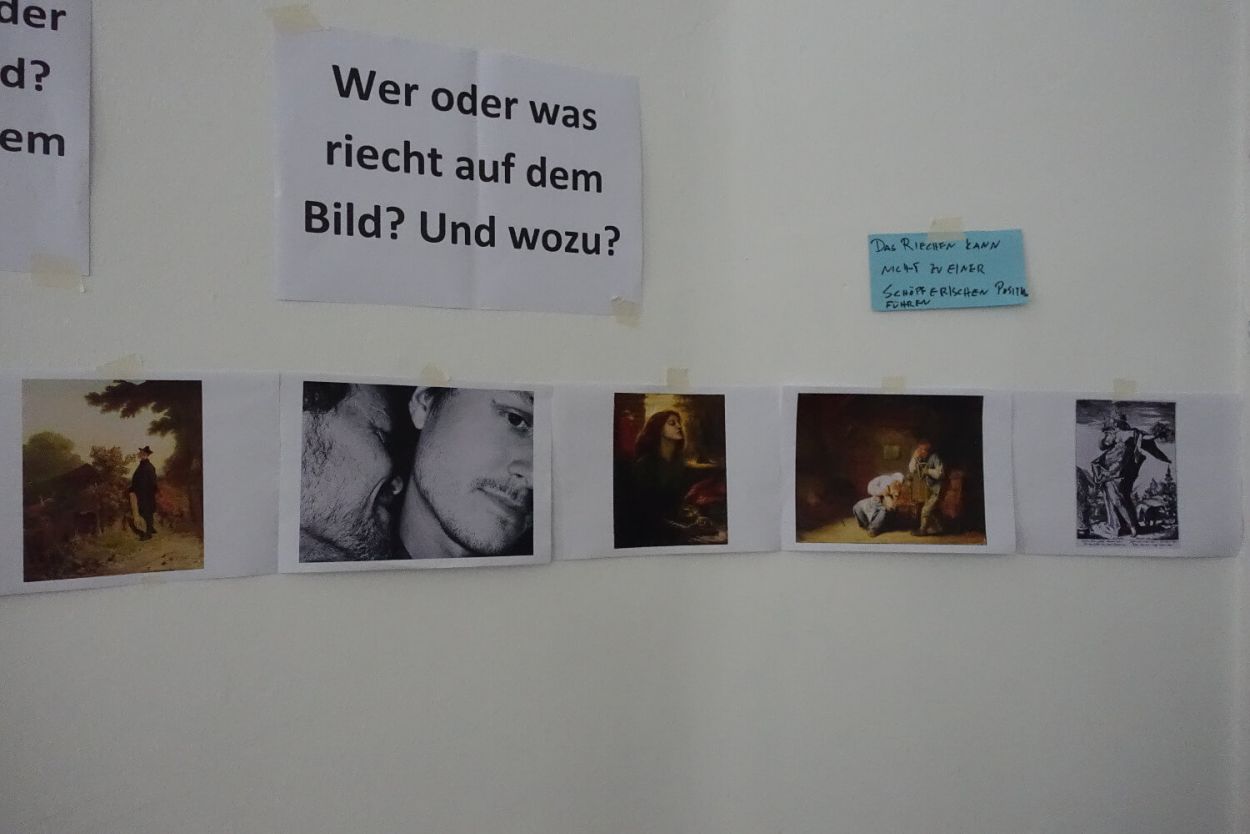

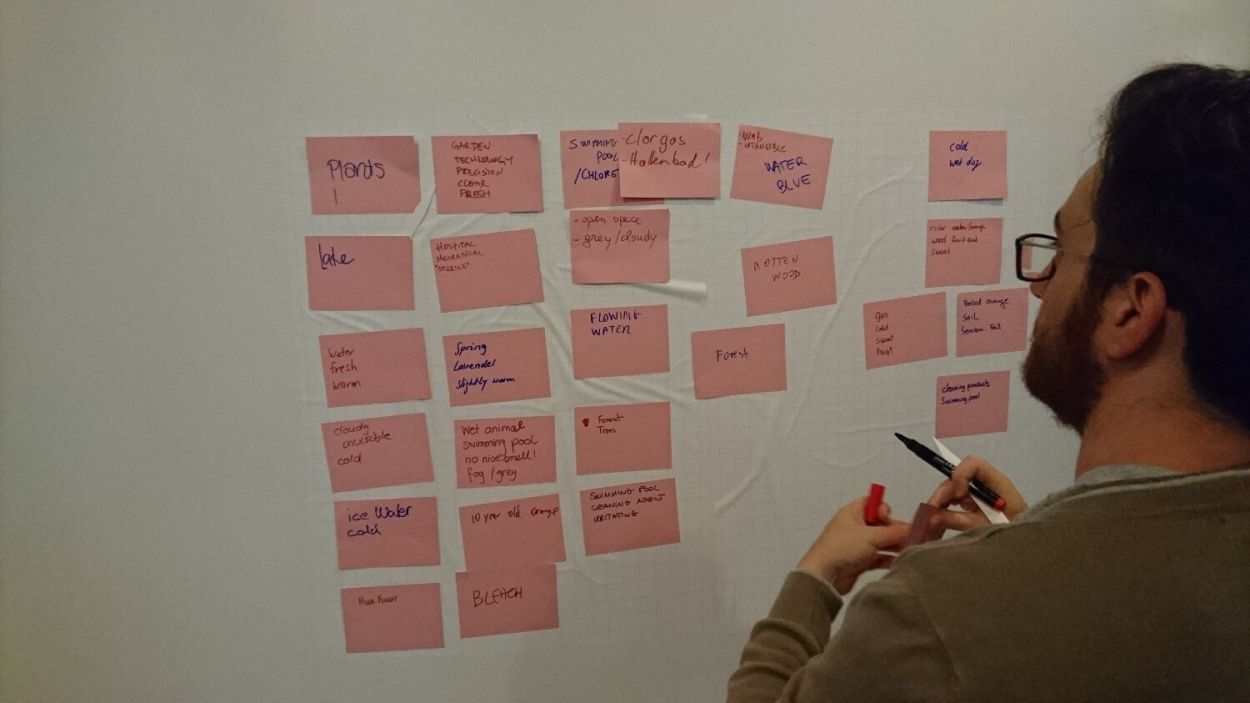

Visual representations of smell-related practices used during a smell culture class at Berlin University of the Arts.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

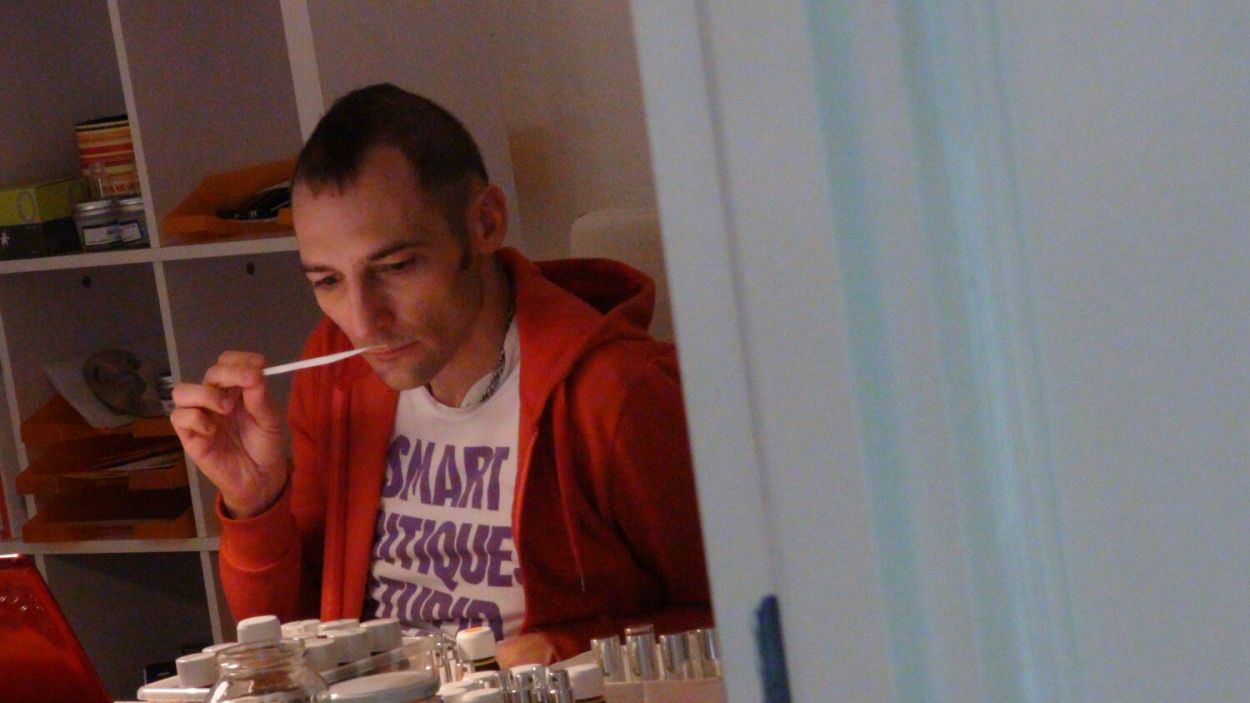

Christophe Laudamiel seeking another nose.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

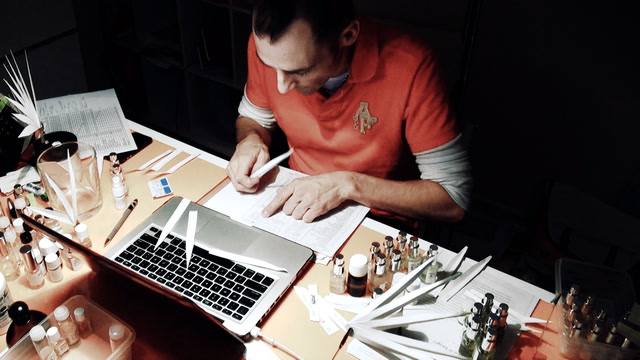

Christoph Hornetz evaluating different resins as a material base. The resins are later used when trying to smell pepper.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Public reading of Tim Krohn’s scent inspired stories at an olfactory storytelling festival, Solothurner Literaturtage, 2019.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel focusing on a modification.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christoph Hornetz & Christophe Laudamiel evaluating combinations of different scents and different resins.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christoph Hornetz’ notes taken while experiencing a smelody, an olfactory sequence, juxtaposed and interwoven with sound and noise, at the Osmodrama festival created by Wolfgang Georgsdorf.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel smelling at his desk.

Courtesy: Brian Goeltzenleuchter

Visitors experiencing Sillage, an olfactory artwork by Brian Goeltzenleuchter in Santa Monica.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

A curious customer checking the «test plan» on her smartphone during trying different perfumes at the Scent Bar on Beverly Blvd in Hollywood.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel smelling a scent on his hand.

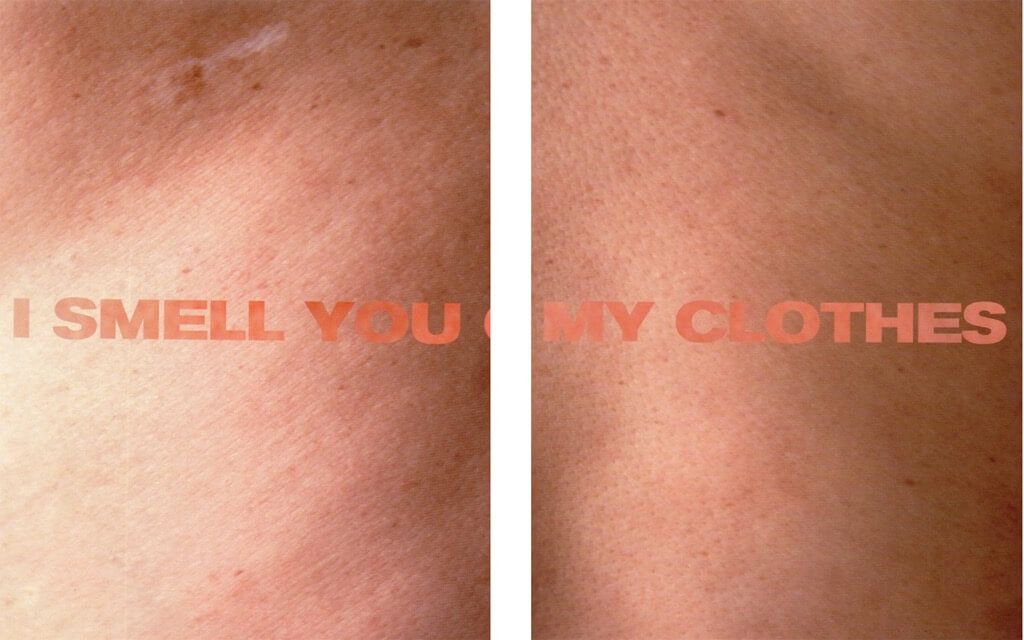

Courtesy of Jenny Holzer & Marc Atlan.

I smell you on my skin: Campaign Helmut Lang Perfumes, 1999/2000. Jenny Holzer & Marc Atlan.

Wikimedia Commons, PD-Art (Yorck Project), CC-PD-Mark, PD-Art (PD-old-70)

Allegorie van de geur by Jan Brueghel the Elder and Peter Paul Rubens.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Sharing impressions from smelling the same single molecule ingredient during a workshop.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

En passant, Christoph Hornetz and Christophe Laudamiel are smelling and sharing first impressions.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Sergey Borisov, editor and columnist with Fragrantica, smelling at the Humiecki & Graef booth at Esxence in Milano.

Photo: Loulou d'Aki

Hunting scent bubbles at Bern Urban Scent Walk, in the context of the 2014 Bern Biennial.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel analyzing a set of modifications. There is a video documenting this type of work further.

WikiArt Visual Art Encyclopedia, CC-PD-Mark

Roses (also known as The Scent of Roses) by Lilla Cabot Perry.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel at his desk - en passant smelling his palms?

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel evaluating multiple modifications.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Students at the University of St.Gallen attending a seminar on smell culture conduct a scent walk on campus.

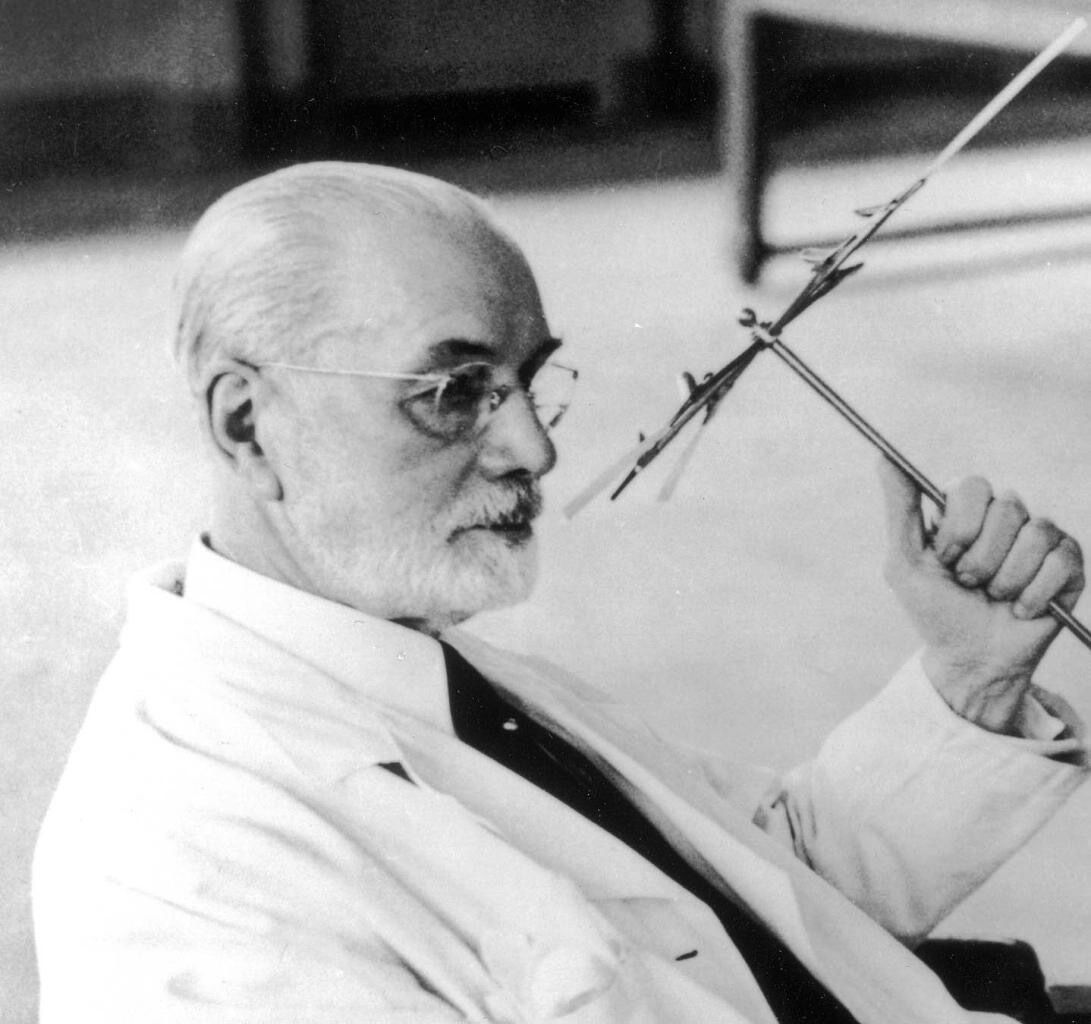

George William Septimus Piesse was a leading author and innovator of modern perfume ideas, coining the term, “notes” in perfumery. Book cover. Piesse, G. W. S. (1857). The art of perfumery and the methods of obtaining the odors of plants. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston.

All Tags

- Affect

- Ambience

- Ambiguity

- Analogy

- Analyzing

- Artifact

- Associating

- Beyond words

- Briefing

- Christophe Laudamiel

- Classifying

- Consuming

- Creating

- Culture

- Deciding

- Desk work

- Embodiment

- Ephemeral

- Ethnography

- Evaluating

- Experimenting

- Hemingway

- Humiecki & Graef

- Industry

- Ingredient

- Interaction

- Labelling

- Laboratory

- Metal

- Modifications

- Mundane work

- Orange Flower

- Paper

- Presenting

- Sense-making

- Shalimar

- Storytelling

- Still life

- Strangelove NYC

- Translating

- Visual

- we are all children

- Words