The power of words1:22

The power of words1:22

Suddenly Christophe discloses the name of an ingredient to the researcher...

The French capucine is commonly known as nasturtium. Its pronunciation in German «Kapuzinerkresse» instantly irritates the perfumer. Hence, the clip reveals factors impacting scent design beyond common textbook wisdom. Even the phonetic sound of an ingredient might make a difference. Christophe’s multisensory approach is perfectly in line with recent scientific findings showing that odor names affect sniffs length, scent familiarity, perception and evaluations. Accordingly, the same scent can be perceived by the same person differently depending on the label attached. Thus, the label «parmesan cheese» positively influences the scent evaluations in comparison with the situation when the scent is labelled as «vomit». Moreover, scent-related words (e.g. strawberry) might be influential for the olfactory experience than non-related words (e.g. old house).

Evaluative moments2:33

Evaluative moments2:33

Three professionals engage in smelling and discussing an advanced modification of Meltmyheart, a fragrance by StrangeLove NYC.

We see how Christophe Laudamiel, Christoph Hornetz and the flavorist Marlene Staiger spontaneously share their impressions and associations. Apparently, there is no one way of evaluating a scent. A closer look reveals how micro-practices of smelling and using blotters can differ. Christophe is particularly interested how the other two experience a certain effect that he describes as «hot metal effect». The subtitles show how the three professionals cannot agree on what the dominant note of this scent smells like: caramel, coconut and hot metal stand next to each other. A shared interpretation of what they are actually smelling seems to be rather unimportant. Yet, something is achieved in this communication. It is neither explicit agreement nor disagreement. Instead it is the affective experience the three professionals express and collectively interpret as «good». And it is this affective experience that might be key to understanding how organizing is accomplished in a creative context. Is it possible that affects really constitute an organization?

Making of Hemingway in 6-Major4:08

Making of Hemingway in 6-Major4:08

An upcoming gallery show changes the rules of the game.

«Clients are the difference between design and art», as a common saying goes. In fact, it is the client who sets the goals, decides on the budget and approves the final scent. Hence, perfumers work under constraints defined by the client whereas creative work is often associated with freedom and autonomy. Yet, constraints can also be helpful because they stimulate creativity rather than suppress it. This clip shows how Christophe copes with a set of self-defined constraints and highlights the importance of independent work for the creative practice. A few days later, the project Hemingway in 6-Major was actually exhibited at a fancy gallery in Chelsea.

(De)briefing a scent2:36

(De)briefing a scent2:36

What is challenging about talking about scents? Can scents have structure? How many dimensions does a scent have?

A meeting with Sebastian Fischenich, the creative director of Humiecki & Graef, provides an opportunity to reflect on the state of the project. The perfumer presents alternative modifications and clarifies next steps with the creative director. In this case the two evaluate alternative scent «structures,» an initially surprising metaphor used to capture the fleeting nature of the olfactory experience.

Step by step6:01

Step by step6:01

There is more than meets the eye

At its core, the practice of perfumery has not changed very much since Renaissance times. The process can be described along a sequence of clearly defined steps: The perfumer starts with some vague ideas which are evoked by certain olfactory ingredients. Thereafter, this rather open process is narrowed down to a precise formula determining the perfume composition in quantitative terms - how much of each material is needed to achieve the ideal balance. Accordingly, the formula is precisely weighed in the laboratory. Each step is accurately documented on a spreadsheet. Using paper strips the perfumer smells and evaluates the scent. Alternative variations are analyzed. The formula is then modified based on detailed analysis. This sequence of steps is repeated until the olfactory experience meets the expectations of the perfumer: Calculating the formula, weighing, evaluating & analyzing.

Nobel laureate Herbert Simon once analyzed how in oil painting every new spot of pigment laid on the canvas creates some kind of pattern that provides a continuing source of new ideas to the painter. Hence, the painting process unfolds as a process of cyclical interaction between the painter and canvas in which current goals lead to new applications of paint, while the gradually changing pattern suggests new goals. In the case of scent development, the cyclical interaction involves the competent use of additional objects (e.g. the formula). However, the practice of perfumery cannot be reduced to this technical dimension. Instead, it is also a meaning and sense-making activity. «To become a perfumer you don’t learn to smell like one – you learn to think like one», Avery Gilbert once noticed. This clip provides a quick primer on this practice.

Key quotes with this tag

Images with this tag

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Working on a scent brief: making notes. A few moments later the search for papery notes unfolds.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

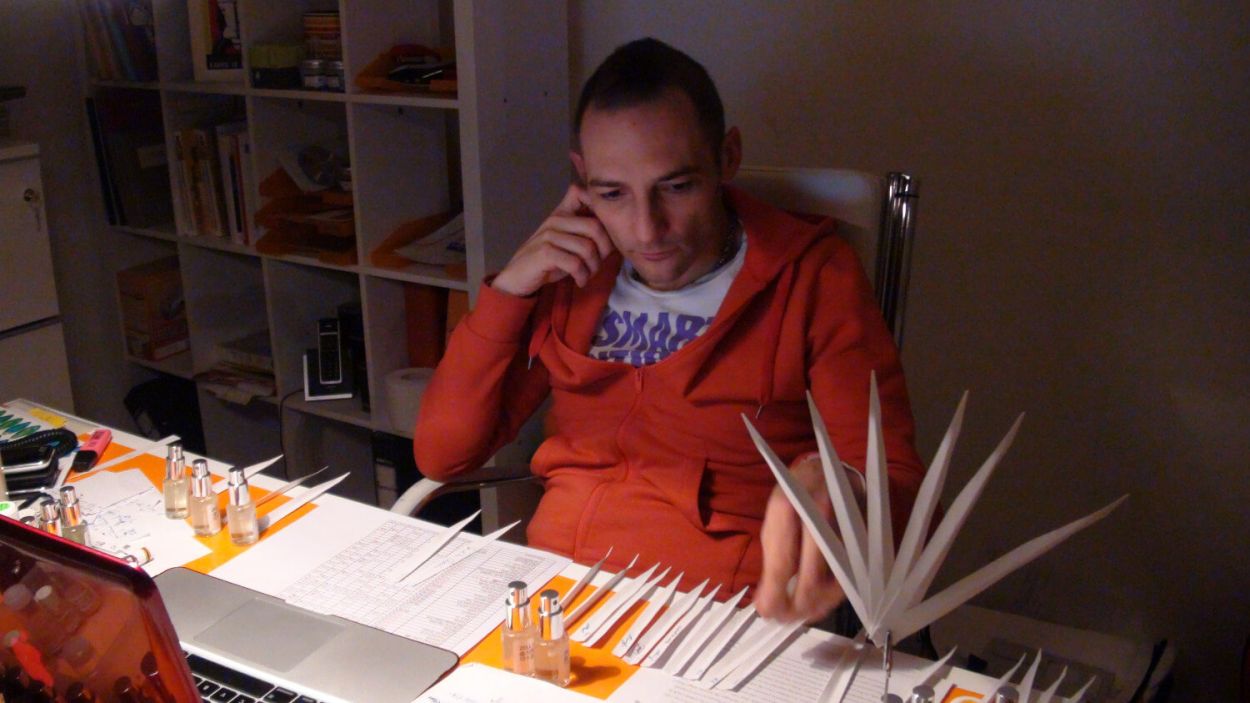

Christophe Laudamiel analyzing a set of modifications. There is a video documenting this type of work further.

Courtesy of scentculture.tube

Christophe Laudamiel smelling two modifications in a relaxed body posture.

All Tags

- Affect

- Ambience

- Ambiguity

- Analogy

- Analyzing

- Artifact

- Associating

- Beyond words

- Briefing

- Christophe Laudamiel

- Classifying

- Consuming

- Creating

- Culture

- Deciding

- Desk work

- Embodiment

- Ephemeral

- Ethnography

- Evaluating

- Experimenting

- Hemingway

- Humiecki & Graef

- Industry

- Ingredient

- Interaction

- Labelling

- Laboratory

- Metal

- Modifications

- Mundane work

- Orange Flower

- Paper

- Presenting

- Shalimar

- Smelling

- Storytelling

- Still life

- Strangelove NYC

- Translating

- Visual

- we are all children

- Words